The integration space is in constant change. Many open source projects and closed source technologies did not withstand the tests of time and have disappeared from the middleware stacks for good. After a decade, however, Apache Camel is still here and becoming even stronger for the next decade of integration. In this article, I'll provide some history of Camel and then describe two changes coming to Apache Camel now (and later to Red Hat Fuse) and why they are important for developers. I call these changes subsecond deployment and subsecond startup of Camel applications.

Gang of Four for integration

Apache Camel started life as an implementation of the Enterprise Integration Patterns (EIP) book. Today, these patterns are the equivalent of the object-oriented Gang of Four Design Patterns but for messaging and integration domain. They are agnostic of programing language, platform, architecture, and provide a universal language, notation, and description of the forces around fundamental messaging primitives.

But the Camel community did not stop with these patterns; they kept evolving and adding newer patterns from service-oriented architecture (SOA), microservices, cloud-native, and serverless paradigms. As a result, Camel turned into a generic pattern-based integration framework suitable for multiple architectures.

Universal library consumption model

Although the patterns gave the initial spark to Camel, its endpoints quickly became popular and turned into a universal protocol for using Java-based integration libraries as connectors. Today, there are hundreds of Java libraries that can be used as Camel connectors using the Camel endpoint notation. It takes a while to realize that Camel can also be used without the EIPs and the routing engine. It can act as a connector framework where all libraries are consumed as universal URIs without a need to understand the library-specific factories and configurations that vary widely across Java libraries.

The right level of abstraction

Some developers will tell you that it is possible to do integration without Camel, and they are right for about 80% of the easy use cases, but not for the other 20% of cases that can turn a project into a multi-year frustrating experience. What they do not realize is that, without Camel, there are multiple manual ways of doing the same thing, but none are validated by the experience of hundreds of open source developers. And, without Camel, an integration project can quickly turn into a bespoke, homegrown framework that nobody wants to work on.

Doing integration is easy, but doing good integration that will evolve and grow for many years, by many teams, is hard. Camel addresses this challenge with universal patterns and connectors, combined with integration focused DSLs, that have passed the test of time.

If you think you don't need Camel, you are either thinking for short-term gains or you are not realizing yet how complex integration can become.

Embracing change

It takes only a couple of painful experiences in large integration projects to start appreciating Camel. But Camel is great not only because it was built on the work of great minds, but also because it evolves thanks to the world's knowledge, shared through the open source model and its networking effects. Camel started as the routing layer in enterprise service buses (ESBs) during the SOA period with a lot of focus on XML, WS, JBI, OSGI, etc., but it was quickly adapted for REST, Swagger, circuit breakers, SAGAs, and Spring Boot in the microservices era.

And, it did not stop there. With containers and Kubernetes, and now serverless architecture, Camel keeps embracing change. That's because Camel is written for integrating changing environments, and Camel itself grows and shines on change. Camel is a change enabling library for integration.

Behind the scene engine

One of Camel's secret sauces is that it is a non-intrusive, unopinionated, small (5MB and getting smaller) integration library without any affinity for where and how you consume it. If you notice, this is the opposite of an ESB, which commonly Camel is confused with because of its extensive capabilities. Over the years, Camel has been used as the internal engine powering projects such as:

- Apache ServiceMix ESB

- Apache ActiveMQ

- Talend ESB

- JBoss Switchyard

- JBoss Fuse Service Works

- Red Hat Fuse

- Fuse Online/Syndesis

- And many other frameworks mentioned here.

You can use Camel alone, embed it with Apache Tomcat, with Spring Boot starters, JBoss WildFly, Apache Karaf, Vert.x, Quarkus, you name it. Camel doesn't care, and it will bring superpowers to your project every time.

Looking to the future

I cannot predict what the ideal integration stack will look like in a decade—no one can. But I can tell you about two novelties coming into Apache Camel now (and to Red Hat Fuse later) and why they will have a noticeable positive effect for the developers and the business. I call these changes subsecond deployment and subsecond startup of Camel applications.

Subsecond deployments to Kubernetes

There was a time when cloud-native meant different technologies. Today, after a few years of natural selection and consolidation in the industry, cloud-native means applications created for container-based environments, such as Kubernetes and its ecosystem of projects within the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. Even with this definition, there are many shades of cloud-native, from running a monolithic non-scalable application in a container, to triggering a function that is fully embracing the cloud-native development and management practices.

The Camel community has realized that Kubernetes is the next generation application runtime, and it is steadily working on making Camel a Kubernetes native integration engine. The same way Camel is a first-class citizen in OSGi containers, Java EE application servers, other fat-jar runtimes, Camel is becoming a first-class citizen on Kubernetes, integrating deeply and benefiting from the resiliency and scalability offered by the platform.

Here are a few of the many enhancement efforts happening in this direction:

- Deeper Kubernetes integration — Kubernetes API connector, full health-check API implementation for Camel subsystems, service discovery through a new ServiceCall EIP, configuration management using ConfigMaps. Then a set of application patterns with special handling on Kubernetes, such as: clustered singleton routes, scalable XA transactions (because sometimes, you have to), SAGA pattern implementation, etc.

- Cloud-native integrations — Support for other cloud-native projects such as exposing Camel metrics for Prometheus, tracing Camel routes through Jaeger, JSON-formatted logging for log aggregation, etc.

- Immutable runtimes — Whether you use the minimalist immutable Apache Karaf packaging or Spring Boot, Camel is a first-class citizen ready to put in a container image. There are also Spring Boot starter implementations for all Camel connectors, integration with routes, properties, converters, and whatnot.

- Camel 3 — Apache Camel 3 is a fact and actively progressing. A big theme for Camel 3 is to make it more modular, smaller, with faster startup time, reactive, non-blocking, and triple awesome. This is the groundwork needed to restructure Camel for the future cloud workloads.

- Knative integration — Knative is an effort started by Google to bring some order and standardization in the serverless world dominated by Amazon Lambda. And Camel is among the projects that integrate with Knative primitives from early days and enhances the Knative ecosystem with hundreds of connectors acting as generic event sources.

And here is a real game-changer initiative: Camel K (a.k.a. deep Kubernetes integration for Camel).

We have seen that Camel is typically embedded into the latest modern runtime where it acts as the developer-friendly integration engine behind the scene. In the same way that Camel used to benefit from Java EE services in the past for hot-deployment, configuration management, transaction management, etc., today Camel K allows Camel runtime to benefit from Kubernetes features for high-availability, resiliency, self-healing, auto-scaling, and basically distributed application management in general.

Camel K achieves this through a CLI and an Operator, where the latter is able to understand the Camel applications, its build-time dependencies, runtime needs, and make intelligent choices from the underlying Kubernetes platform and its additional capabilities (from Knative, Istio, OpenShift, and others in the future). It can automate everything on the cluster, such as picking the best-suited container image and runtime management model and updating them when needed. The CLI can automate the tasks that are on the developer machine, such as observing the code changes, streaming those to the Kubernetes cluster, printing the logs from the running Pods, etc.

Camel K operator understands two domains: Kubernetes and Camel. By combining knowledge of both areas, it can automate tasks that usually require a human operator.

The really powerful part is that, with Camel K, a Camel route can be built and deployed from source code to a running Camel route on Kubernetes in less than a second.

Forget about making a coffee, or even having a sip, while building and deploying a Camel route with Camel K. As soon as you make changes to your source code and open a browser, the Camel route will be running in Kubernetes. This will have a noticeable impact on the way the developers write Camel code, compile, drink coffee, deploy, and test. Apart from changing development practices and habits, this toolset will significantly reduce the development cycles, which will be noticed by the business stakeholders, too. For a live demonstration, check out this awesome video from Fuse engineers working on Camel K project.

Subsecond startups of Camel applications

A typical enterprise integration landscape is composed of stateless services, stateful services, clustered applications, batch jobs, file transfers, messaging, real-time integrations, and maybe even blockchain-based business processes. To that mix, today, we also have to add serverless workloads, which are best suited for event-driven use cases.

Historically, the heavy and slow Java runtime had significant drawbacks compared to Go, Javascript, and other light runtimes in the serverless space. That is one of the main motivations for Oracle to create GraalVM/Substrate VM. Substrate VM is a framework that enables ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation of Java applications into native executables that are light and fast. Then a recent effort by Red Hat led to creation of the Quarkus project, which further improves resource consumption, startup, and response times of Java applications mind-blowingly (a term not used lightly here).

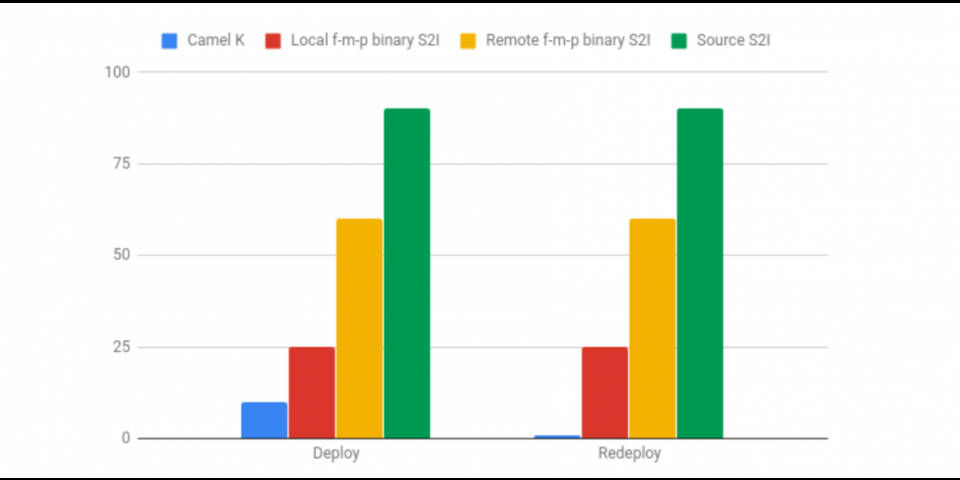

As you can see from the metrics above, Quarkus combined with SubstrateVM is not a gradual evolution. It is a mutation and a revolutionary jump that suddenly changes the perspectives on Java’s footprint and speed in cloud-native workloads. It makes Java friendly for serverless architecture. Considering the huge Java ecosystem of developers and libraries, it even turns Java into the best-suited language for serverless applications. And, it makes Camel, combined with Quarkus, the best-placed integration library in this space.

Summary

With the explosion of microservices architecture, the number of services has increased tenfold, which gave birth to Kubernetes-enabled architectures. These architectures are highly dynamic in nature and are most powerful with light and fast runtimes that enable instant scale up and higher deployment density.

Camel is the framework to fill the space between disparate systems and services. It offers data consistency guarantees, reliable communication, failover, failure detection and recovery, and so on, in a way that makes developers productive. Now, imagine the same powerful Apache Camel-based integration in the year 2020 that deploys to Kubernetes in 20ms, starts up in 20ms, requires 20MB memory, and consumes 20MB on the disk. That is regardless of whether it runs as a stateless application in a container or as a function on Knative. That means 100x faster deployments to Kubernetes, 100x faster startup time, 10x less resource consumption allowing real-time scale-up, scale-down, and scale to zero.

These are changes that developers will notice during development, users will notice when using the system, and businesses will notice on the infrastructure cost and overall delivery velocity. That is the real cloud-native era we have been waiting for.

Last updated: July 25, 2023