The IT self-service agent AI quickstart connects AI with the communication tools your team already uses, including Slack, email, and ServiceNow. This post explores how the agent handles multi-turn workflows—such as laptop refreshes or access requests—across different channels.

This agent is part of the AI quickstarts catalog, a collection of ready-to-run, industry-specific use cases for Red Hat AI. Each AI quickstart is simple to deploy and extend, providing a hands-on way to see how AI solves problems on open source infrastructure. Learn more: AI quickstarts: An easy and practical way to get started with Red Hat AI

Users can interact with a single AI agent across several channels without losing context. For example, a user can start a request in Slack, follow up by email, and trigger actions in ServiceNow. We integrated these tools into the core architecture to ensure a consistent experience across platforms.

This is the second post in our series about developing the it-self-service-agent AI quickstart. Catch up on the rest of the series:

- Part 1: AI quickstart: Self-service agent for IT process automation

- Part 2: AI meets you where you are: Slack, email & ServiceNow

- Part 3: Prompt engineering: Big vs. small prompts for AI agents

Why integration is the real problem

Most enterprise AI systems start from the model outward. They focus on prompts, tools, and responses, then bolt on an interface at the end. That approach works fine for demos, but it breaks down quickly in real environments.

In many organizations enterprise work is fragmented:

- Slack is where questions start and evolve.

- Email is where updates, approvals, and follow-ups still live.

- ServiceNow is where work becomes official and auditable.

Forcing users into a single "AI interface" just creates another silo. The goal of this AI quickstart is the opposite: to meet users where they already work and let the AI adapt to them, not the other way around.

That decision has architectural consequences. Slack, email, and ServiceNow all behave differently. They have different identity models, delivery semantics, and interaction patterns. Treating them as interchangeable doesn't work—but treating them as completely separate systems doesn't either.

A unifying architecture

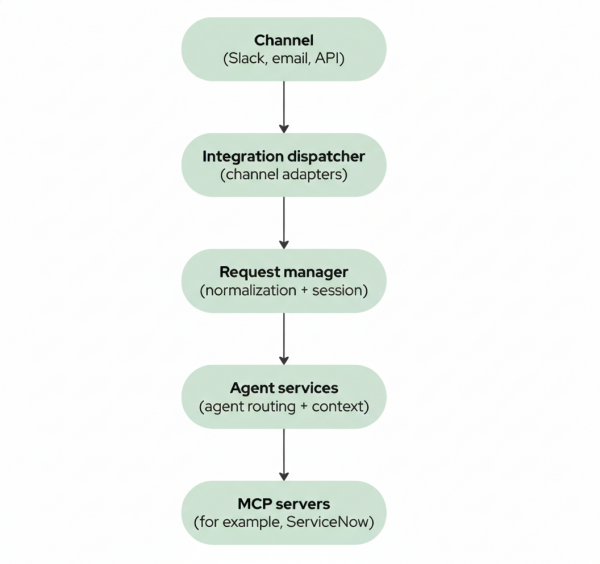

At a high level, every interaction flows through the same core path as shown in in Figure 1. The request begins at a channel—such as Slack or email—and passes through an integration dispatcher using channel adapters. From there, it moves into a request manager for normalization and session handling, then through agent services for routing and context, before finally reaching the MCP servers (such as ServiceNow).

Each integration adapter is responsible for handling protocol-specific details—verifying Slack signatures, polling email inboxes, parsing headers—but that logic stops at the boundary. Once a request is normalized and associated with a user session, the rest of the system treats it the same way regardless of where it came from.

This separation keeps the agent logic focused on intent, policy, and workflow orchestration instead of UI or transport details. It also makes the system extensible: new integrations don't require rewriting the agent.

But how do these services actually communicate? That's where CloudEvents comes in.

CloudEvents: The communication layer

All inter-service communication uses CloudEvents, a standardized event format (Cloud Native Computing Foundation specification) implemented as HTTP messages. This enables the scalability and reliability that enterprise deployments require.

CloudEvents provides three key benefits: scalability, reliability, and decoupling.

Scalability comes from the event-driven model. Services don't block waiting for responses. The request manager can publish a request event and return immediately, while the agent service processes it asynchronously. This means the request manager can handle many more concurrent requests than synchronous processing would allow.

Reliability comes from durable message queuing. If the agent service is temporarily unavailable, events queue up and are processed when the service recovers. This is critical for production deployments where services might restart, scale, or experience temporary failures.

Decoupling means services don't need to know about each other's implementation details. The request manager publishes events with a standard format, and any service that subscribes can process them. This makes it easy to add new services—like a monitoring service or audit logger—without modifying existing code.

The system supports two deployment modes that use the same codebase. In production, we use Knative Eventing with Apache Kafka for enterprise-grade reliability. For development and testing, we use a lightweight mock eventing service that mimics the same CloudEvents protocol but routes events via simple HTTP. The same application code works in both modes—only the infrastructure changes.

Here's an example of a CloudEvent published to the broker:

{

"specversion": "1.0",

"type": "com.self-service-agent.request.created",

"source": "integration-dispatcher",

"id": "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000",

"time": "2024-01-15T10:30:00Z",

"datacontenttype": "application/json",

"userid": "user-uuid-abc123",

"data": {

"content": "I need a new laptop",

"integration_type": "slack",

"channel_id": "C01234ABCD",

"thread_id": "1234567890.123456",

"slack_user_id": "U01234ABCD",

"slack_team_id": "T01234ABCD",

"metadata": {}

}

}Knative Eventing's abstraction layer, combined with CloudEvents, enables platform flexibility. The application code just publishes and consumes CloudEvents to a broker URL—it doesn't know or care about the underlying broker implementation. While the current deployment uses Kafka, Knative Eventing supports other broker types (like RabbitMQ or NATS) through different broker classes.

Switching brokers requires updating a Kubernetes configuration, but no application code changes. For example, to switch from Kafka to RabbitMQ, you'd change the broker class annotation, as shown in the following YAML:

# Switch to RabbitMQ

apiVersion: eventing.knative.dev/v1

kind: Broker

metadata:

annotations:

eventing.knative.dev/broker.class: RabbitMQThe services still send CloudEvents to the same broker URL—only the infrastructure behind it changes.

Session continuity across channels

Different integrations use different identifier formats (Slack uses user IDs like U01234ABCD, email uses addresses), and email addresses don't always match across systems or change independently. To enable session continuity, we use a canonical user identity—a UUID that maps to all integration-specific identifiers. This gives us a stable anchor that doesn't break when identifiers change.

Sessions in this system are user-centric by default, not integration-centric. That means a single active session can span Slack, email, and other channels (web, CLI, webhooks). A user can:

- Start a request in Slack

- Receive updates by email

- Reply to that email later

- Continue the same conversation without restating context

This behavior is what makes the system feel unified rather than stitched together. Without it, you'd effectively be running separate systems for each channel. There's a configuration option to scope sessions per integration type if needed, but in practice, cross-channel sessions are what users expect.

The canonical identity approach also enables extensibility: when adding a new channel (like Teams or SMS), you just map its identifiers to the canonical UUID, and sessions automatically work across all channels without additional session management logic.

Session resolution happens early in request handling. If a request includes an explicit session identifier (for example, via email headers), it's used. Otherwise, the system looks for an active session for that user and reuses it. New sessions are created only when necessary.

Slack: Conversational by design

Slack is usually the front door. It's real-time, interactive, and event-driven. The Slack integration handles:

- Signature verification and replay protection

- User resolution from Slack IDs to canonical users

- Translation of messages, commands, and interactions into normalized requests

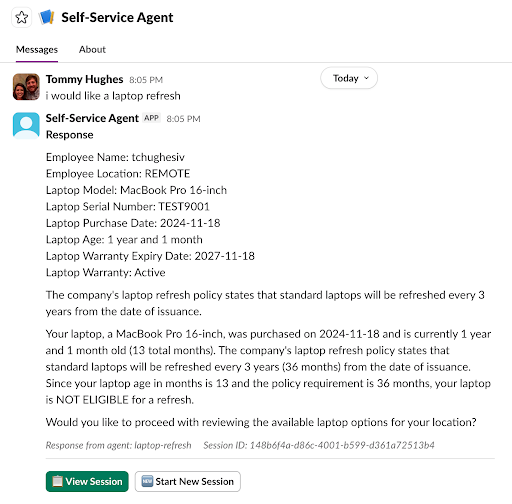

Figure 2 shows an example of an interaction in Slack.

Slack-specific features—threads, buttons, modals—are handled entirely within the adapter. The agent never needs to know how a button click is represented in Slack; it just receives structured intent.

This design keeps Slack interactions responsive and rich while preventing Slack assumptions from leaking into the rest of the system. It also allows the integration to safely handle retries and duplicate events, which are a reality of Slack's delivery model.

Email: Asynchronous but persistent

Email plays a different role. It's not conversational in the same way Slack is, but it's still critical—especially for long-running workflows and notifications.

Rather than forcing email into a chat metaphor, the system treats it as a continuation and notification channel. Email is used to:

- Deliver agent responses (which may include summaries, status updates, or requests for action)

- Provide an asynchronous alternative to real-time channels—critical for IT workflows where ticket updates and approvals often happen via email

- Allow conversations to resume after delays, matching how IT ticketing systems typically operate

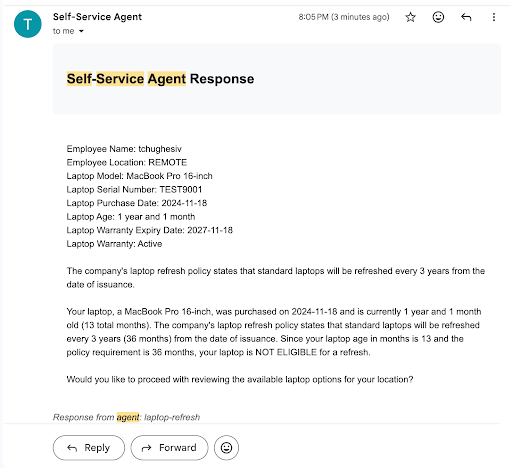

Figure 3 shows an example of an interaction via email.

Outgoing emails include session identifiers in headers and message bodies. Incoming email is polled, deduplicated, and correlated back to existing sessions using those identifiers and standard threading headers.

From the user's perspective, replying to an email "just works." From the system's perspective, it's another request in an existing session.

The request manager: Normalization and control

At the center of all this is the request manager. Its job is not to reason about intent—that's the agent's responsibility—but to ensure that requests are:

- Normalized into a consistent internal format

- Associated with the correct user and session

- Logged and deduplicated

- Routed to the appropriate agent

This normalization follows object-oriented encapsulation principles: The NormalizedRequest object encapsulates integration-specific complexity behind a unified interface. The agent service processes all requests identically—it never needs to know whether a request came from Slack, email, or a CLI tool. Integration-specific details (like Slack's channel_id or email's threading headers) are preserved in integration_context for response routing, but hidden from the core processing logic. This abstraction boundary is what makes the system extensible: adding a new integration doesn't require modifying any downstream services.

It's also where we enforce idempotency and prevent duplicate processing—an unglamorous but essential part of building something that survives real-world usage.

Each integration type has its own request format—Slack requests include channel_id and thread_ts, email requests include email_from and email_in_reply_to headers, CLI requests have command context. The RequestNormalizer transforms all of these into a single NormalizedRequest format that the rest of the system understands.

The following simplified pseudocode illustrates how Slack requests are normalized (the actual implementation includes additional error handling and context extraction):

def _normalize_slack_request(

self, request: SlackRequest, base_data: Dict[str, Any]

) -> NormalizedRequest:

"""Normalize Slack-specific request."""

integration_context = {

"channel_id": request.channel_id,

"thread_id": request.thread_id,

"slack_user_id": request.slack_user_id,

"slack_team_id": request.slack_team_id,

"platform": "slack",

}

# Extract user context from Slack metadata

user_context = {

"platform_user_id": request.slack_user_id,

"team_id": request.slack_team_id,

"channel_type": "dm" if request.channel_id.startswith("D") else "channel",

}

return NormalizedRequest(

**base_data,

integration_context=integration_context,

user_context=user_context,

requires_routing=True,

)This abstraction makes it easy to add new integrations—you just need to create a new request schema and add a normalization method. The rest of the system automatically works with the new integration because it only deals with NormalizedRequest objects.

You can find the full implementation with support for Slack, Email, Web, CLI, and Tool requests in it-self-service-agent/request-manager/src/request_manager /normalizer.py.

The request manager is stateless in terms of conversation context—it delegates that to the agent service. But it's stateful in terms of request tracking and session management, which enables the cross-channel continuity we need.

The agent service uses LangGraph with PostgreSQL checkpointing to persist conversation state. Every turn of the conversation—messages, routing decisions, workflow state—is saved to the database, allowing conversations to resume exactly where they left off. The request manager coordinates this by maintaining session records that map user identities to LangGraph thread IDs. When a request arrives from any channel, the request manager retrieves the associated thread ID and passes it to the agent service, which resumes the conversation from its last checkpointed state.

This checkpointing is what makes multi-turn agentic workflows possible across channels and time gaps. Without it, you'd be rebuilding conversation state from scratch on every request, which breaks the continuity that makes agentic systems feel intelligent rather than stateless. A user can start in Slack, continue via email days later, and return to Slack without losing context—because the conversation state persists independently of the channel.

Integration dispatcher: Delivering responses reliably

Incoming requests are only half the story. Delivering responses is just as important.

The integration dispatcher is responsible for sending agent responses back out through the appropriate channels. It supports:

- Multichannel delivery (Slack, email, webhooks)

- Smart defaults (users don't need to configure everything up front)

- User overrides for delivery preferences

- Graceful degradation if one channel fails

If Slack delivery fails, email can still succeed. If a user has no explicit configuration, sensible defaults are applied dynamically. This "lazy configuration" approach reduces operational overhead while still allowing full customization when needed.

ServiceNow and MCP: Turning conversation into action

Slack and email are about interaction. ServiceNow is where work happens in many organizations.

Interactions by the agent with ServiceNow are handled with a dedicated Model Context Protocol (MCP) server. This creates a clean, enforceable boundary:

- Authentication and credentials are isolated.

- Allowed operations are explicit.

- Side effects are controlled and auditable.

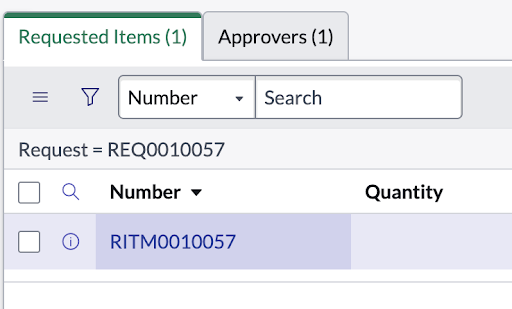

Figure 4 shows an example of an interaction with ServiceNow.

The agent reasons about what needs to happen; the MCP server controls how it happens. This separation improves safety and makes integrations easier to evolve.

The same pattern applies to other backend systems. Once identity and session context are established, the agent can interact with operational systems in a controlled, extensible way.

A deeper dive into MCP design and extension patterns will be covered in a later post in this series.

What this enables

Putting all of this together enables a few important outcomes:

- Lower friction: Users stay in tools they already use

- Continuity: Conversations survive channel switches and time gaps

- Real work: Requests result in actual tickets and system changes

- Extensibility: New integrations fit naturally into the architecture

- Maintainability: Channel logic stays separate from agent logic

This comes from treating integration, identity, and sessions as core architectural concerns.

Get started

If you're building AI-driven IT self-service solutions, consider how your system will integrate with existing tools. The AI quickstart provides a framework you can adapt for your own use cases, whether that's laptop refresh requests, access management, compliance workflows, or other IT processes.

Ready to get started? The IT self-service agent AI quickstart includes complete deployment instructions, integration guides, and evaluation frameworks. You can deploy it in testing mode (with mock eventing) to explore the concepts, then scale up to production mode (with Knative Eventing and Kafka) when you're ready.

Closing thoughts

"Meeting users where they are" isn't just a design slogan; it's an architectural commitment. The IT self-service agent AI quickstart shows that this is achievable using open source tools and an intentional design. This approach results in an AI that fits into existing workflows rather than just providing isolated responses.

Where to learn more

If this post sparked your interest in the IT self-service agent AI quickstart, here are additional resources to explore.

- Browse the AI quickstarts catalog for other production-ready use cases including fraud detection, document processing and customer service automation.

- Questions or issues? Open an issue on the GitHub repository or file an issue.

- Learn more about the tech stack: