Recommender systems are everywhere. Whether in retail, entertainment, social platforms, or embedded into enterprise marketing software, recommender systems are the invisible engine in modern markets, driving efficiency on both sides of the supply-demand equation. Every day they help consumers find their way through millions of options in the digital world to quickly find the products and services they want, while for businesses, they help product, sales and marketing teams to align and match their company's offerings with potential customers.

To build and maintain effective recommender systems, software engineers must manage significant challenges, like technical complexity, privacy, and security. Furthermore, they must ensure these systems remain scalable while delivering on high-quality intelligent recommendations and semantic search. This article looks at the Red Hat AI Product Recommender AI quickstart and walk through how Red Hat OpenShift AI helps engineers tackle these challenges.

Product recommender AI quickstart

AI quickstarts are sample applications that demonstrate how Red Hat AI products, such as OpenShift AI, provide a platform for your AI applications. While not intended as production-ready solutions, they demonstrate how engineers can integrate key OpenShift AI technologies and third-party libraries to build modern AI-enabled applications.

Learn more: Introducing AI quickstarts

This AI quickstart demonstrates how Red Hat OpenShift AI helps organizations boost online sales and reshape product discovery by implementing these core AI-driven business functions:

- Machine learning (ML) models that make accurate product recommendations

- Semantic product search capabilities using text and image queries

- Automated product review summarization

This series is organized into three parts:

- Part 1: AI technology overview and background (this post)

- Part 2: Understanding the recommender system's two-tower model

- Part 3: AI-generated product review summaries and new user registration

Overview of AI technologies that support the recommender

In this section, we provide an overview of the technologies our AI quickstart is built on, while subsequent sections are reserved for in-depth coverage. Figure 1 shows these technologies.

LLMs and machine learning models

Working clockwise from the top left in Figure 1, the AI quickstart relies on advanced LLMs and ML models to perform key functions. Specifically, the AI quickstart uses the four models described in Table 1.

| Model | Function |

|---|---|

| BAAI/BGE-small-en-v1.5 text embedding model | Converts product descriptions, titles and other text to embeddings (lists of numbers) to enable semantic search. |

| openai/clip-vit-base-patch32 image embedding model | Embeds product images to enable image-based queries. |

| Llama 3.1 8B | Generates product review summaries. |

| Two-tower recommender model | Provides product recommendations. |

Engineers must consider many factors when choosing ML models, but the most important ones are the task and type of data the model supports. The AI quickstart uses the first two models in Table 1 on the embedding task for text and image data. These models accept chunks of text and images and produce numeric representations that align with their semantic content. For example, embeddings for two different cell phone models are closer together than embeddings for a cell phone and a blender. The AI quickstart uses this proximity to enable robust search that returns accurate matches despite minor variations in the input. We discuss embeddings in greater detail later in this article.

The AI quickstart uses the Llama 3.1 8B model on the generative task for text inputs. Specifically, the AI quickstart prompts the model to summarize the reviews for each product. Like the first two models in Table 1, the Llama 3.1 model is an LLM (large language model), but its decoder-only architecture is designed to generate tokens sequentially in response to instructions, whereas the first two models are encoder-only models better for creating embeddings.

The final model in our list is the two-tower model, which is another embedding model except that it bears a dual-encoder architecture. This model knows how to represent products and users as embeddings in a coordinated fashion that reflects how well these two entities interact with each other. We will make this idea much clearer in part 2 of this article.

Though engineers don't always need to train ML models from scratch, as is the case with the first three models in Table 1, they nonetheless need to manage their acquisition, storage, metadata, evaluation and runtime use. OpenShift AI provides a complete suite of integrated technologies designed to manage these tasks across various roles within development teams, including data scientists, ML engineers and MLOps specialists. These technologies are integrated into OpenShift to help enterprises use existing infrastructure investments to build AI-enabled applications with centralized security, governance, and resource provisioning.

Our AI quickstart and this article focus only on a subset of these technologies, including workbenches (familiar Jupyter notebooks) that support model acquisition and evaluation, the Red Hat inference server that stands up LLMs as scalable services, Feast for managing product and user features (including embeddings), and the OpenShift AI pipeline server built on Kubeflow Pipelines and Argo Workflows to manage model training.

Workbenches

Workbenches support data scientists and ML engineers by enabling the rapid creation of Jupyter notebooks within the OpenShift cluster. OpenShift offers preconfigured notebook images—including Data Science, TensorFlow, PyTorch, and TrustyAI— to support the full ML lifecycle from model acquisition to prototyping. Administrators can also supplement these with custom images. Part 3 explores how workbenches facilitate moving models from external registries (such as the Red Hat AI repository on Hugging Face) into enterprise-controlled, S3-compatible storage. While direct deployment from OCI-compliant images is possible, workbenches allow engineers to first evaluate and improve model performance with techniques like quantization.

Inference servers

The ML models in Table 1 are static in nature; i.e., they lack the means to generate text, make predictions or create the data representations we require for semantic search. The models only represent the patterns they've learned over their training data as structured collections of billions of numbers. To apply these patterns to unseen data samples and application tasks, we need libraries that can load these numbers into memory and run computations over them.

OpenShift AI achieves this in several ways and, moving to the right in Figure 1, we see that inference servers play a critical role. Inference servers are to machine learning models what database query engines are to static datasets. They respond to user queries to generate answers using the available data. Most importantly, they do this efficiently for thousands of concurrent requests while keeping each query and response isolated from one another and secure from unauthorized access.

A naïve approach that processes one request at a time would lead to long wait times and an inconsistent user experience. This would be like waiting in a long grocery line behind full shopping carts when you only have a few items.

To solve this, OpenShift AI uses continuous batching. Instead of finishing one customer's entire cart before moving to the next, the system processes one item from every customer's cart in a continuous cycle. When paired with accelerators like NVIDIA GPUs or Intel Gaudi, this technique ensures the hardware remains active so users get results faster.

In short, OpenShift AI's inference server, together with the KServe framework, takes otherwise static ML models and turns them into scalable services on an OpenShift cluster.

Feature store

Our AI quickstart's core recommender model as well as its semantic and image search capabilities directly rely on the consistent management of user and product features. Features are data elements like product descriptions and user preferences in our user and product database tables. Because ML models learn only from prior experience or data, the features used during training must match those used later during inference; otherwise, accuracy suffers through a phenomenon known as training-serving skew.

This is often a more serious and likely outcome than system designers initially anticipate. Within most organizations, data constantly evolves in often subtle ways that don't cause applications to break outright but instead introduce subtle errors that go undetected.

Feast is a feature store that works with a number of vector databases, like Postgres in our case, to provide a single-source-of-truth to define and version features, allowing data to evolve to meet the needs of new applications or requirements without breaking existing applications.

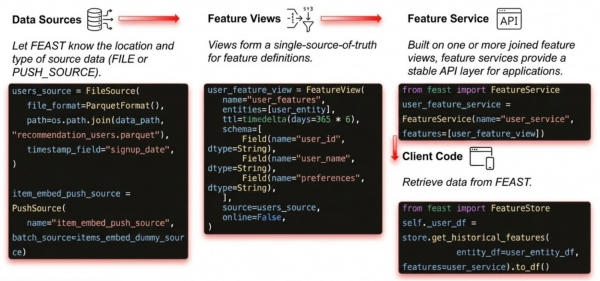

Feast also provides a unified Python API for working with feature data through concepts like data sources, views and services. Figure 2 depicts the following usage pattern our AI quickstart uses:

- A data source is defined (for example, a parquet file bundled with the application or a live data source that changes at runtime)

- A subset of columns is defined on this data source to create a view

- A FeatureService is created on this view

The client code sample in Figure 2 shows how, once these API objects are defined, clients retrieve data using a consistent interface.

Model training pipeline orchestration

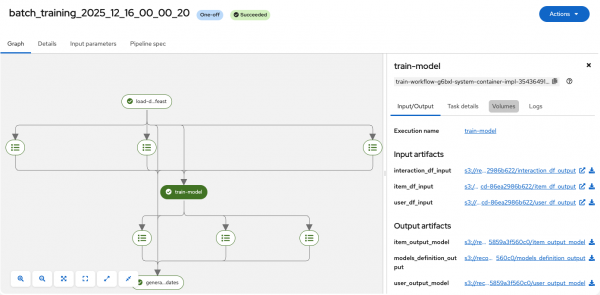

Before we can serve the AI quickstart's core recommender model, we need a framework to manage its training workflow. OpenShift AI provides a flexible approach that covers common and advanced ML training workflows (called pipelines) using Kubeflow Pipelines (KFP) and a workflow engine like Argo Workflows. Pipelines are simply batch jobs we are already familiar with in computer science, except with important updates that adapt their use for machine learning in modern containerized environments. Figure 3 shows the OpenShift AI dashboard view of the pipeline that builds the two-tower recommender model, providing visibility into each run's execution logs and data flow across its training stages.

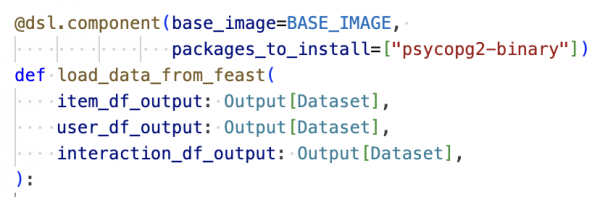

Engineers can describe pipelines and their components through Python decorators (the approach our quickstart uses and as shown in Figure 4) or Elyra (Figure 5).

Figure 4 shows the Python function signature for load_data_from_feast, the first stage in building the recommender model. Pipeline components are regular Python functions decorated with the Kubeflow Pipeline (KFP) DSL (domain specific language); for example, @dsl.component. KFP uses these tags to free developers from the lower-level details of configuring and deploying their pipeline to focus instead on the pipeline's core training logic. In Figure 4, for example, we see how the engineer has indicated the load_data_from_feast function can use a configured baseline container image with one additional Python package. KFP takes care of creating a container from this image and installing the required dependency when the training job is executed. We will discuss KFP in greater detail in part 2.

Engineers can also explore beyond our AI quickstart to use Elyra, a user interface (UI) driven front-end to KFP that Red Hat has integrated with data science workbenches. Elyra enables engineers and data scientists to drag and drop their Jupyter notebooks onto a blank canvas where they can connect them together to quickly build training pipelines.

Semantic search

Now that we've provided a background on the components of OpenShift AI the Product Recommender AI quickstart uses, let's dive deeper into the AI quickstart's semantic search capabilities, beginning with a quick review of semantic embeddings.

Embeddings primer

To work with text and images, ML models must first convert them to lists of numbers called vectors. For example, the sequence <1.2, 3.1, -0.3> illustrates a vector with three components or numbers. One way to think of these numbers is as geometric points in high-dimensional space. Our sample picks out a unique point in only three dimensions, but imagine taking this idea further to 384 dimensions, the vector size that the BGE-small model generates (Table 1). It's intuitive to see that these additional dimensions may help us capture more information, but for these high-dimensional geometric points to be useful at all, we must set their values so they model our semantic notions of products and users. We need the vectors to form an embedding space.

An embedding space applies these vectors in a coordinated way such that the distance between the vectors for similar words is small but also such that the addition or subtraction of these vectors is meaningful. For example, we would like the vectors that describe our products to support the following arithmetic:

Vector(‘Trail Hiker's Backpack') + Vector(‘Upgrade') ≅Vector(‘Mountaineer's Backpack')

Neural networks learn embedding spaces by processing pairs of input data known to be similar or dissimilar or related in some other way, like question and answer pairs. The network slowly modifies its internal weights until the vectors for related pairs are close together and those for unrelated pairs are farther apart. Modern embedding models (like the BGE-small model) are encoder-only LLMs that can represent fine shades of meaning between similar words and handle polysemy, which occurs when a single word has multiple meanings depending on the context. This process of contrastive learning can be applied to create image embeddings and, as we discuss shortly, our AI quickstart's recommendation model.

Search by text and image

Our AI quickstart consists of a main landing page which displays product recommendations to authenticated users as well as a semantic search capability across all its product catalog using text and image queries. The representation of both queries and product data as embeddings enables text matching that is robust to semantically similar variations in product descriptions, like "thin remote controls" versus "slim remotes." Similarly, the image search capability enabled by the CLIP model in Table 1 can successfully match images of the same object even with different lighting or angles.

Our AI quickstart enables semantic text search and image search by computing and storing embeddings for its product catalog in advance. At runtime, the application generates an embedding for the user's query and uses Feast's API to locate products with similar embeddings.

To be precise, for text queries, the AI quickstart employs what's known as hybrid search, a general technique which combines semantic matching with traditional regular expressions. This results in more intuitive ranking in search results that pushes exact text matches to the top of the list where most users would expect to find them. Hybrid search is also useful in applications that already provide a well-defined database structure for certain types of queries. For example, consider an online clothing retailer that lets users filter search results by age group using a drop-down menu; for example, clothing for children, teens, or adults. If the system already uses a dedicated typed field to store this distinction in its product database, then a simple SQL filter is preferred over a semantic match for this aspect of the user's query.

Two-tower model: Recommendations as a search problem

Given what we've discussed about embeddings, it might seem tempting to apply them to generate product recommendations; for example, we could use our embedding model to represent a user's attributes (such as product category preferences) as a vector and then search for products with similar vectors (using product attributes like their descriptions and categories). This would effectively convert our core recommendation task to a much simpler search problem which we know Feast can already handle.

However, this idea only works when the two vectors are part of the same embedding space; otherwise, the relative geometric positions of the vectors are not meaningful. Imagine trying to meet a friend at a restaurant for lunch using a pair of shared coordinates. If you're using a map with standard latitude and longitude coordinates while your friend is relying on a tourist's map using a simpler 20x20 integer grid centered on the city's airport, you probably will end up in different places. The numbers and distances on the two maps do not relate to each other.

Our two-tower model addresses this problem using a custom dual encoder which builds this shared embedding space.

In part 2 of this series, we look deeper into how the two-tower model is trained and how OpenShift's KFP integration helps engineers so they don't have to tackle it alone. Read it here: Understanding the recommender system's two-tower model

Last updated: February 2, 2026