In my time working in the software industry, I have encountered recurring issues involving versioning. Which version scheme should we use for project X? When should we bump the major version? Is this pull request a breaking change? We want to cut a new release, but what should the next version be?

Versioning schemes communicate new features, bug fixes, and even breaking changes to our users. Some schemes are like a contract with users, giving them guarantees for types of version changes. For instance, a major version bump from version 2.4 to 3.0 usually implies a breaking change and a substantial new functionality. Consumers of software (e.g., Linux distributions) can decide when and how to use the new versions.

But not all versioning schemes are equal. Some schemes are more expressive than others. My personal favorite is semantic versioning, which I will elaborate on later in this article. Other versioning issues are naming and tagging container images. This topic comes up all the time in communications with customers, partners, and the community.

In this article, I will share my lessons learned about naming, tagging, and versioning container images and software. Being decisive in answering the following questions will prevent future headaches and make our lives easier. Are we in control over changes? Which changes can we expect from updates? Is the latest tag any good? What are the advantages and disadvantages of referencing an image by digest? What is semantic versioning? I will attempt to provide answers to these questions and more.

What is an image reference

Let’s discuss terminology before digging into the details of naming and tagging conventions, versioning schemes, and digests.

We rarely ask ourselves which version, tag, or digest to use when working with containers—at least on our workstations. As outlined in an earlier article, container engines such as Podman allow for a great user experience by resolving short names to a real reference of a container image. For instance, doing a podman pull fedora will pull the registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora:latest image. I love that experience on my workstations because I don’t have to type much and Podman knows better where to pull an image.

However, we should be more careful when moving our workloads to production. Choosing the wrong tag may result in future downtimes and hours of debugging. To make sure we are all on the same page, let’s look at the different parts of a container image reference, as shown in Figure 1.

A reference can contain a domain (quay.io) pointing to the container registry, one or more repositories (also referred to as namespaces) on the registry (fedora), and an image (fedora-bootc) followed by a tag (41) and/or digest (sha256). Note that images can be referenced by tag, digest, or both at the same time, as shown in Figure 1.

Repository organization

Typically, you would scope a registry configuration to repositories (or their parents), so a single repository should contain related images. There are two common ways of organizing repositories:

The most common method is to use a repository to store all versions of a single container image, storing all versions of that application. For example,

registry.example/my-frontend:v1.0,registry.example/my-frontend:v1.1, andregistry.example/my-frontend:v2.0. A larger distributed application would then use a collection of repositories, one repository per container image (registry.example/my-frontend,registry.example/my-backend,registry.example/my-database).An alternative method is to distribute the whole distributed application in a single repository, using a more detailed tag convention or digest references (described next) to distinguish between different images. This is the case for Red Hat OpenShift that ships most of the core container images of the product in

quay.io/openshift-release-dev/ocp-v4.0-art-dev.

What is an image tag

A tag points to an image on a given registry and repository. There is no strict enforcement on how to use tags, but there are certain conventions. For instance, tags are frequently used to version images (e.g., fedora:40, fedora:41). In the early container days, tags were also used to ship a given image in multiple architectures (e.g., image:version-arm64, image:version-s390x).

An important attribute of tags is that they are mutable. A given tag may point to a specific image today but can point to another updated image in the future.

Should you use the latest tag

As a convenience to users manually entering commands in a CLI, container engines default to using the latest tag if the user has not provided a tag or digest. By convention, it is expected that the latest tag points to the most recent image, so defaulting to it makes sense for a great user experience. When we run podman run fedora, we just want to get the latest and greatest version of Fedora without worrying about the exact details. This is perfect for an interactive experience.

But should we use the latest tag in production? My general answer is no. Today, the tag may point to Fedora 41, but it will certainly point to another version in future with potentially breaking changes to the workload.

In the end, it boils down to understanding the stability and support guarantees of the given name and tag we use. As an end user, we have no control over the changes going into the Fedora latest tag. But if we are building an image on our own and have full control and ownership over the changes going in, it is perfectly fine to use the latest tag.

When deciding which tag to use, we must consider whether we are in control over the images we consume and if we are at risk of running into breaking changes at some point. Using the latest tag is certainly tempting because it is easy and straightforward, but we need to be aware of what we’re up against.

What is an image digest

In contrast to a tag, a digest guarantees which image we will consume. I previously discussed the digest in reference to fully-qualified image references. A digest refers to a specific image on a registry, which means the target can never change. To clarify, the digest is the sha256sum of the JSON image metadata.

What’s so special about digests? A tag is a pointer that can direct to any image and change over time, but a digest identifies exactly one image, namely the one with the matching sha256sum on the registry and namespace. Pulling an image by digest will fail if there is no matching image on the registry.

Let’s do a quick experiment to highlight the nature of a digest. For that purpose, we'll use Skopeo, a container image tool. Skopeo is like a Swiss Army Knife for all things related to container images and has been dedicated to the CNCF in late 2024 along with Podman, Podman Desktop, bootc, and Buildah.

As mentioned, the digest is the sha256sum of the JSON metadata of a given image. We can query the metadata via skopeo inspect. The following shows the digest specified to the image is the exact sha256sum:

$ skopeo inspect --raw docker://fedora@sha256:3ec60eb34fa1a095c0c34dd37cead9fd38afb62612d43892fcf1d3425c32bc1e | sha256sum

3ec60eb34fa1a095c0c34dd37cead9fd38afb62612d43892fcf1d3425c32bc1e -This exercise demonstrates that we will get exactly the requested image when using a digest.

When to use a digest

I recommend referencing an image by digest when you need to be in full control over which image to use. This can be beneficial in production use cases where we use and run the one image that has been fully tested and released. We could use a tag, but the digest has the additional benefit of being unique. The tag points to an image that may always change, intentionally or accidentally.

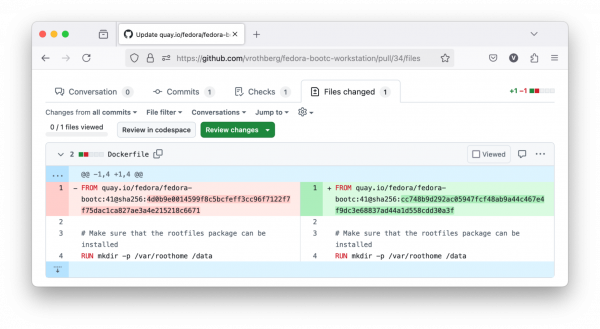

The main idea is to be aware, intentional, and control the images we consume and the image changes. In an article about CI/CD pipelines for Image Mode for RHEL, we elaborated on the benefits of referencing an image by digest to achieve a GitOps-like workflow to build and manage bootc images in a fully automated fashion. Dependency-management bots will automatically open a pull request to update the digest in our Containerfile, so we have full control of the changes. We are making use of this setup to manage a bootc-based workstation here. Figure 2 illustrates automated digest updates to a Dockerfile.

In summary, referencing an image by digest expresses the intent to use one specific image. Using a digest renders container builds more reproducible since every build will always use the same base image. A digest further prevents certain pitfalls and human error caused by the ambiguity of tags, and it has certain security benefits since we will only use the exact image requested. You should consider using a digest when you want to solve these issues.

When to use a tag

Tags are essential to referencing container images. We've already discussed the benefits of using digests, but those are better for machines. A tag is a way to communicate the contents, version, support, and lifecycle of an image to users.

Let’s consider the fedora:41 image. By looking at the name Fedora and the tag 41, it is obvious that the tag is the specific version of Fedora. This tells us exactly how long the image will receive updates as the container image follows the documented lifecycle of the Fedora project.

When should you use a tag? It depends on the use case, requirements, and the target environment. It is crucial to consider which changes we may consume. A tag is only a pointer to an image and can be updated at any time. The 41 tag of the Fedora image will point to another image (i.e., a new digest) whenever the project releases new updates to the image by rebuilding and publishing it.

Using the 41 tag guarantees that there won’t be any breaking changes during the lifetime of this version of Fedora, so running workloads with this tag is totally acceptable. The low risk of a potential accidental breaking change to an image resulting in breaking my workload isn't worth the additional work of constantly updating the digest to consume updates and security fixes.

Finding the right balance is also important. Would I reference an image only by tag if my life depended on it? Absolutely not. I would always use a digest. Would I use a tag for my streaming service at home? Absolutely.

Note that there are other means than using a tag to embed a version. For example, Red Hat’s Universal Base Image embeds the version in the repository registry.redhat.io/ubi9/ubi.

Best practices for tagging and versioning images

When it comes to publishing and releasing images, make sure clients can easily consume them. Choosing the right tagging and versioning schemes for your images will pay off in the long term since it impacts workload management. Semantic versioning is an expressive strategy for tagging images.

Semantic versioning is like a contract for consumers, using the format X.Y.Z, where incrementing either component has a very specific (semantic) meaning:

- X: A major version bump with backwards incompatible changes.

- Y: A minor version bump with new functionality and backwards compatible changes.

- Z: A patch version bump with bug fixes but without new functionality in a backwards compatible way.

Using semantic versioning has many advantages over using less expressive versioning schemes such as the latest tag. One advantage is the version of a given image is obvious. Another advantage is that consumers of the image can pin to major and/or minor versions. For instance, using image:2.3 will pin to the version 2.3 and consume all patch updates (e.g., 2.3.1, 2.3.2, etc). Using image:2 will pin to the major version 2 including all minor and patch versions (e.g., 2.1, 2.2, etc). Using image:2.3.1 would pin to this exact version and not include future patch versions.

Note that your release pipelines must ensure that the X.Y tags are floating and continuously updated when releasing a patch version.

The importance of container image versioning

In summary, there is no best method for consuming, publishing, and referencing container images. There are many best practices out there. Whether we rely on tags, digests, semantic versioning, or other versioning schemes and naming conventions, it all boils down to being decisive about what we publish and consume. Our use cases, requirements, and the degree of automation should determine what’s best in a given environment. I hope that this article will help you navigate this space.

Last updated: January 29, 2025