By following my previous article in this series, you've crushed the whole containers thing. It was much easier than you anticipated, and you've updated your resume. Now it's time to move into the spotlight, walk the red carpet, and own the whole Kubernetes game. In this blog post, we'll get our Kubernetes environment up and running on macOS, spin up an image in a container, and head to Coderland.

The parts

Unlike a certain brand of kitchen cabinets that I recently purchased that had instructions only as diagrams with a stick figure person and some numbers and arrows, we'll lay out the items and steps with diagrams and words. We need:

- A way to run containers

- Kubernetes

- The Kubernetes command-line tool,

kubectl. - The

occommand-line tool for Red Hat OpenShift - An image to run as a test.

A way to run containers

We need some sort of environment to run containers. Options include Minikube, CodeReady Containers, and a Red Hat OpenShift cluster (running on, say, AWS). We'll keep things simple and forward-looking by choosing CodeReady Containers (abbreviated as "CRC"). This will run on our local machine yet give us the power of Kubernetes (and OpenShift, by the way) without spending any money.

That's always nice.

So let's install CodeReady Containers on macOS. It's five steps.

Installing CodeReady Containers

- Visit the CodeReady Containers downloads page and download the latest macOS-compatible release. Keep this page open; you'll need it for the step five.

- Uncompress the file. The easiest way to do this is to double-click on the file, or use

tar. - Make sure the file is where you want it to reside (e.g., ~/crc directory).

- Make sure the directory is in your system PATH.

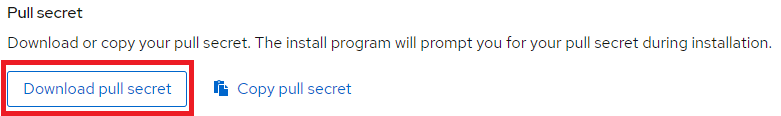

- While you at the CodeReady Containers downloads page, go ahead and download the pull secret; the button is just a bit further down the page. This will be used for authentication the first time you start your Kubernetes (OpenShift, actually) cluster.

It looks like this:

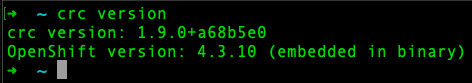

Prove it

The command crc version should yield:

Note that, depending on when you do this, you may have a newer version than shown here.

Installing Kubernetes

Bonus: It's included in CRC. Wow, that was easy.

Installing kubectl

The Kubernetes command-line tool, kubectl, is a breeze to install on macOS:

brew install kubernetes-cli

(If that fails, there is a more in-depth explanation on the kubectl installation page.)

Installing oc

brew install openshift-cli

(Or, you can use the DIY instructions at the okd page. OKD is the upstream version of OpenShift. What is this upstream talk all about? It's part of Red Hat's strategy.)

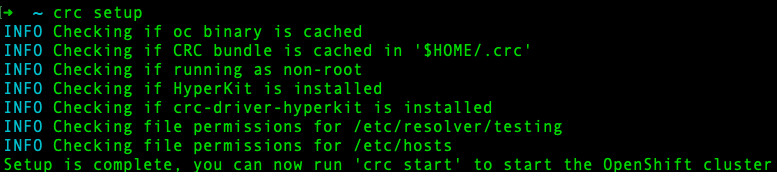

Set it up

Before you can start using CRC, you need to initialize it. There are several option you can set, such as how much memory and number of CPUs, but to keep it simple let's go with the defaults. Use the following command:

crc setup

Fire it up

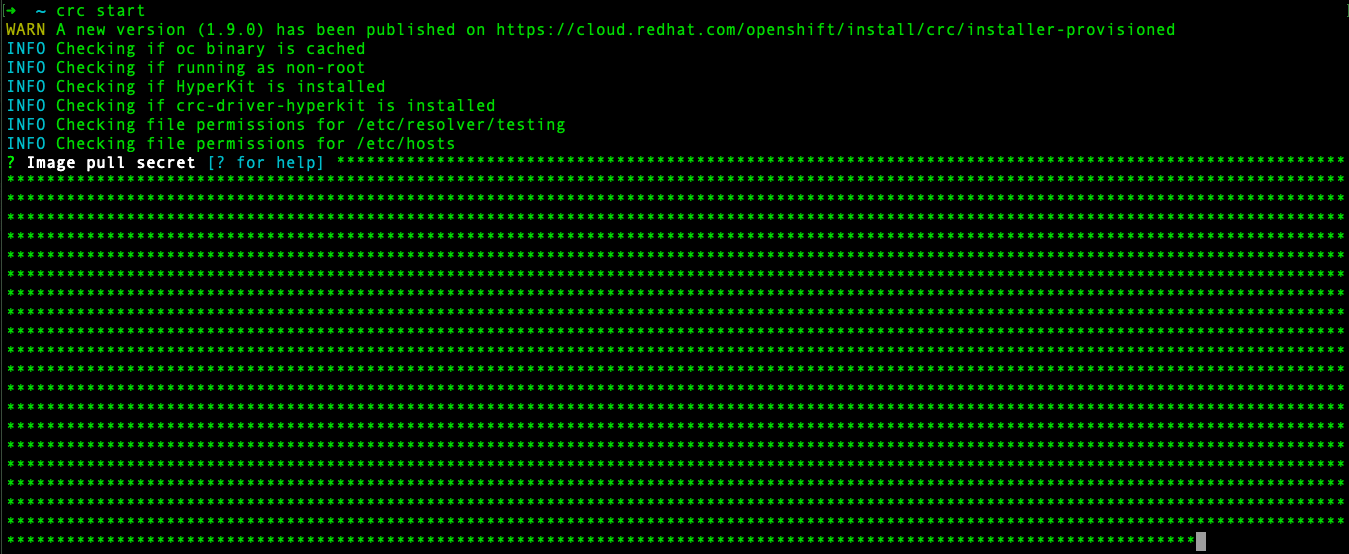

Time to get your cluster up and running. It's one command, but, you'll need your "pull secret" first. Copy it to your Mac's clipboard so you can paste it into the terminal window.

It's quite simple; at the command line, use the following command:

crc start

You will be prompted for your pull secret. Paste it to the command line. Then mash the Enter key and CRC will start.

Note: If, at any time, you want to start fresh with CRC, use the commands crc stop and crc delete --force --clear-cache. You'll need to run crc setup after that.

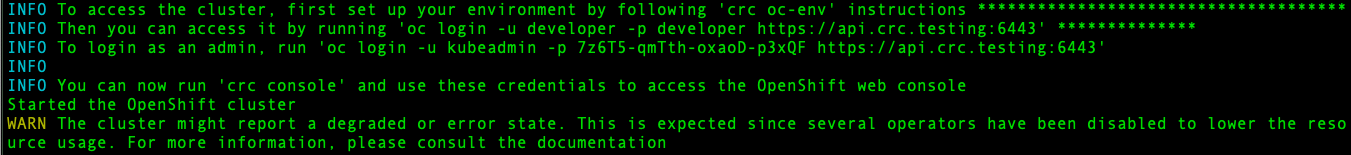

Be patient, it takes a few minutes.

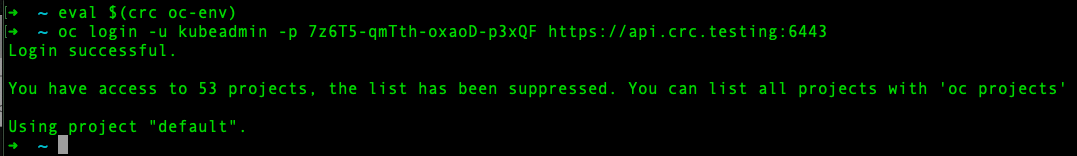

When that finishes, we need a few commands to get "attached," if you will, to our cluster. We're going to cheat here and use some OpenShift commands. Those commands are shortcuts. If we didn't use them, we'd have to alter our Kubernetes configuration and create a user and grant access. We can save a ton of steps. If you want to use only kubectl and be a purist, you can follow this blog post "Logging Into a Kubernetes Cluster With Kubectl." Lucky for us, the login instructions are displayed right there on the screen. You might want to save it for the sake of convenience. If you don't, and you need to log in, the only workaround will be to stop and then again start the cluster.

eval $(crc oc-env) oc login -u kubeadmin -p 7z6T5-qmTth-oxaoD-p3xQF https://api.crc.testing:6443

An image to run

Finally, it's a good idea to run a very basic image as a Kubernetes pod to test your setup. To do this, let's run an image in a pod and then run curl to make sure it's all working as expected.

Use this command to spin up a pod:

kubectl run qotd --image=quay.io/donschenck/qotd:v2 --port=10000

This will pull an image down from my public repository to your system and run it using Kubernetes.

A little more detail: This creates a pod named qotd, retrieves the image, starts the image in a container, and uses port 10000 to route to it. Note that the pod name and the name of the image do not need to match. This is an area where you want to put some management thought into place. In other words, this is a great opportunity to make things really confusing if you're not thoughtful. Don't ask how I know this.

Note that waiting for this pod to get up and running might take a few minutes, depending on your machine's performance. When done on a server or high-performance PC, it takes about a minute or so. My MacBook Air with the i5 processor takes about four minutes. You can check on it by running kubectl get pods.

When the pod is up and running, you cannot access it from your command line. Why is that? Because it's running "inside" your Kubernetes cluster. However, Kubernetes is smart and provides a proxy to your pods in Kubernetes because there may be several containers running the same application; a pod of containers. All with the same URI. When you run kubectl get pods you can see your qotd pod.

Reaching the application

There are two aspects, if you will, to the proxy that Kubernetes has created. One aspect is the proxy itself. The other aspect is the public face of the proxy, that which allows you to access your pods. In other words, the proxy runs on port 8001, while the proxy routes are what allow you to reach your application.

To test the proxy and its access to your pod is a two-step process. Not to worry; this gets much better and much easier later. But for now, we must start the proxy and then access the pod through the proxy. You'll need to open a second terminal window to do this.

In the first terminal window, run the following command:

kubectl proxy

The proxy is running. This will tie up the command line (i.e., it runs interactively), so you need a second terminal window to run the following command, which will return a list of the proxy routes:

curl http://127.0.0.1:8001

Wow. Those results. Those are all the routes built into the Kubernetes proxy. And that's the thing: We're not reaching our application yet ... just the proxy.

The endpoint that leads to our application is /api/v1. The format we want is api/v1/namespaces/{our namespace}/pods/{pod name}/proxy/.

The {our namespace}, in our particular instance, is test.

The pod name can be found, again, by running kubectl get pods. In our example it's qotd.

Put those pieces together and you can reach our application from your second terminal (remember: kubectl proxy is still running in our first terminal window):

curl http://127.0.1:8001/api/v1/namespaces/test/pods/qotd/proxy/

Let's have some fun

The application has several endpoints. Give them a try:

/version

/quotes

/quotes/random

/quotes/1

By the way...

By the way, qotd is written in Go. The magic of containers: (almost) all development languages are welcomed.

Wait, there's more

Although you now have a Kubernetes cluster running on your local machine, there's still a lot more to know and do. There must be an easier way to get to your application than running kubectl proxy in a second terminal. There must be a way to run more than one container, or more than one application. There must be a way to update your code while it's running—a "rolling update" as it's known.

And there is. We'll cover all that as the series continues. In the meantime, own that red carpet.

P.S. It's pronounced "kube-cuddle."