Getting started with Backstage on Kubernetes has never been easier, thanks to Red Hat Developer Hub. Don’t believe me? Watch the 4-minute video in my article showing the Fastest Path to Backstage on Kubernetes, and you might change your mind.

After deploying Red Hat Developer Hub as your internal developer portal (IDP), you should enrich it with the plugins and Software Templates that will make it a truly valuable tool for your developers. This article provides essential insights and tips to help you craft better Software Templates that boost developer productivity.

As a bonus, I will provide links to resources that demonstrate how to deploy Red Hat Developer Hub locally for a faster Software Template development loop. Let's dive in!

Templating fundamentals

Software Templates tell Backstage how to automate chores. Platform engineers can craft templates to enable developer self-service. For example, a developer could use a project or team’s custom template to provision cloud resources or create a new Git repository. The template makes it easier for the developer and it ensures resources, skeleton code, and deployment targets adhere to the organization’s best practices for creating microservices, configuring CI/CD, and enforcing security.

So, how does this work? Software Templates are defined in YAML, like everything else in this cloud-native world we live in. The key elements of a template are the parameters and steps that define the inputs and actions Backstage’s scaffolder (template engine) will request and execute. Figure 1 demonstrates an example of a flow that a developer goes through when utilizing a template to create a new application.

The following YAML represents the flow demonstrated in Figure 1. It creates a Java microservice codebase based on an existing template, stores it in a Git repository with the given name, and displays the URL to the newly created repository when finished. A platform engineer will load this template into Backstage either using the UI or by adding a link to it in the catalog section of the Backstage configuration file.

apiVersion: scaffolder.backstage.io/v1beta3

kind: Template

metadata:

name: create-java-microservice

title: Java Microservice

description: Creates a Java Microservice that follows best practices

spec:

owner: platform-engineering

type: microservice

parameters:

- title: Name

required:

- name

properties:

name:

title: Name

type: string

description: Unique name for the Component, and resulting Git repository

maxLength: 50

pattern: '^([a-zA-Z][a-zA-Z0-9]*)(-[a-zA-Z0-9]+)*$'

ui:autofocus: true

steps:

- id: generateSource

name: Generate Application Codebase

action: fetch:template

input:

# Template code location

url: https://github.com/your-org/template-codebases/java-microservice

# Local directory used to store generated code

targetPath: ./source

# Variables passed to Nunjucks when it renders the

# new files in the source folder from the template

values:

name: ${{ parameters.name }}

- id: publishSource

name: Create Source Code Repository on GitHub

action: publish:github

input:

allowedHosts: ['github.com']

description: ${{ parameters.description }}

repoUrl: github.com?owner=your-org&repo=${{ parameters.name }}

defaultBranch: main

sourcePath: ./source

output:

links:

- title: View the Source Repository

url: ${{ steps.publishSource.output.remoteUrl }}

Software Templates can do more than bootstrap Git repositories. Creative platform engineering teams provide templates to provision cloud resources using GitOps, trigger CI pipelines, open PRs to request approvals and much more. Take a look at the Backstage plugins directory to find plugins that expose scaffolder actions you can utilize to create your own templates.

10 Backstage template tips

Now, I will demonstrate 10 tips for improving Backstage Software Templates:

- Structuring your template repository

- Experimenting with the template editor

- Exploring installed actions

- Improving DevEx using custom field extensions

- Processing structured data using template filters

- Using the Nunjucks API

- Protecting Secrets

- Specifying the template type and tags

- Documenting your templates

- Planning for maintenance

Tip #1: Structure your template repository

Like everything in Backstage, Software Templates are entities (the YAML you reviewed in the prior section) that are imported into the software catalog. Generally speaking, the YAML representing templates is stored in a Git repository. Platform engineers configure their Backstage instance to import the templates.

An organization beginning its journey with internal developer portals and platform engineering is best served by creating a central repository to store templates. Popular convention stores each template.yaml in a subfolder with its assets and documentation. A location.yaml at the root of the repository can use a Location Entity with glob pattern to instruct Backstage to import templates from each subfolder.

This pattern reduces the repetitive task of importing each new template to the Backstage instance individually by simply committing the new template. Then it will appear in the software catalog within a few minutes once the location.yaml is referenced in your Backstage catalog configuration.

templates-repository/

├─ location.yaml

├─ nodejs-backend/

│ ├─ template.yaml

│ ├─ README.md

│ └─ skeleton/

├─ react-frontend/

│ ├─ template.yaml

│ ├─ skeleton/

└─ java-microservice/

├─ template.yaml

├─ skeleton/NOTE: The skeleton directory contains a template codebase that the Backstage scaffolder (template engine) will process using Nunjucks (more on this later) if you’re using the fetch:template action. Samples are available upstream in backstage/software-templates Git repository.

The Backstage templates repository demonstrates a sample implementation of this pattern. Organizations that need more granular control over template authorship and access might choose to create additional template repositories that split templates by knowledge domain or organizational boundaries.

Tip #2: Experiment using the template editor

Pushing changes to a template repository, waiting for Backstage to synchronize the changes, and then doing a test run of changes is an inefficient development loop. A better approach is to use the Template Editor included in Backstage, and by extension, Red Hat Developer Hub.

The template editor can be accessed by visiting the /create/edit page directly, or by using the Template Editor link on the Software Templates page, as shown in figure 2.

You can use the Template Editor to:

- Edit templates stored in a directory on your development machine (or one that you copy/paste into the editor).

- Edit a sample template.

- Experiment with edits to existing templates in your Backstage instance.

- Experiment with installed Custom Field Extensions (more on these in a moment).

Figure 3 shows a platform engineer experimenting with edits to a template, and seeing the changes rendered on the right. Once they’re happy with the changes, they can copy them to their template.yaml.

Tip #3: Explore installed actions

As mentioned earlier, Backstage includes built-in actions and supports actions provided by plugins. You can view available actions and their inputs and outputs by visiting the Installed Actions page via the Software Catalog or the /create/actions page directly.

Figure 4 shows the view platform engineer might see if the Quay Plugin is installed. It can be referenced in a template using the action: quay:create-repository syntax, expects name, visibility, description, and token input parameters.

Use the Installed Actions page to understand the actions that are available to template authors in your Backstage instance.

Tip #4: Improve DevEx using custom field extensions

Forms rendered based on Software Templates are powered by react-jsonschema-form (rjsf). This provides platform engineers with a great deal of flexibility in how they collect the input parameters for their templates. However, Backstage also provides a Custom Field Extensions API that enables platform engineers to further enrich their templates with custom inputs.

If you’re wondering why this might be necessary, consider a scenario where a template asks a user to assign an owner to a new component. Manually typing the group name is error-prone, so the platform engineer uses the built-in OwnerPicker Custom Field Extension to present a dropdown that contains valid options. An example of this is shown in Figure 5.

Tip #5: Process structured data using template filters

Backstage Template Filters are functions that operate on objects in your templates. For example, consider the previous custom field extensions that return Entity References as strings. A template might collect a reference to a component using an EntityPicker field as follows:

properties:

component:

title: Component

type: string

description: The Component you wish to deploy

ui:field: EntityPicker

ui:options:

allowArbitraryValues: false

catalogFilter:

kind: ComponentThe resulting value of ${{ params.component }} will have the format component:namespace/component-name. Actions in the template can use the parseEntityRef filter to extract properties from the entity reference, such as the namespace or name, as follows.

id: openPullRequest

name: Create Pull Request

action: publish:github:pull-request

input:

repoUrl: github.com?repo=your-repo&owner=your-org

title: "Update for ${{ parameters.component | parseEntityRef | pick('name') }}"

commitMessage: "Adds some amazing new functionality"

sourcePath: ./

targetPath: ./${{ parameters.component | parseEntityRef | pick('name') }}

There is a complete example of using parseEntityRef in this sample template.

Tip #6: Use the Nunjucks API

As previously discussed, templates that use the fetch:template action can generate content based on a skeleton. All files in the skeleton are processed using the Nunjucks templating language. Values can be passed to the skeleton by passing values as inputs to the fetch:template action.

id: generateSource

name: Generate Next.js Application

action: fetch:template

input:

# The skeleton folder is in the same repository and folder

# as this template.yaml file, so a relative path works!

url: ./skeleton

targetPath: ./source

values:

name: ${{ parameters.name }}

owner: ${{ parameters.owner }}

system: ${{ parameters.system }}

description: ${{ parameters.description }}These values can be used in skeleton files by accessing the values object. For example, the name can be injected using the ${{ values.name }} syntax, as seen in this example package.json.

However, replacing values is the most basic functionality provided. Nunjucks provides tags to perform operations on your templates. Tags such as if and for can be used to implement conditional logic based on user provided properties and iterating over values. The raw tag can be used to preserve blocks of content. A common scenario where raw is useful is when you need to preserve content as-is, such as variables in a GitHub Actions workflow. Failure to use raw would result in empty values replacing the values in the following example, instead of preserving these values per the template author’s intent.

- name: Log in to the Container registry

uses: docker/login-action@v3

with:

{% raw %}

registry: ${{ env.REGISTRY }}

username: ${{ github.repository_owner }}

password: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

{% endraw %}Tip #7: Protect Secrets

Collecting sensitive data, such as a password or authentication token, as a template parameter needs to be handled carefully. While it might be tempting to use a regular text input field, the correct approach is to use the Secret field provided by Backstage.

The Secret field ensures that the value entered by the end-user in Backstage is masked, as shown by the Template Editor in Figure 6. Additionally, the value is masked in logs and the Review screen before the the scaffolder processes the template. This prevents inadvertent leaking of credentials.

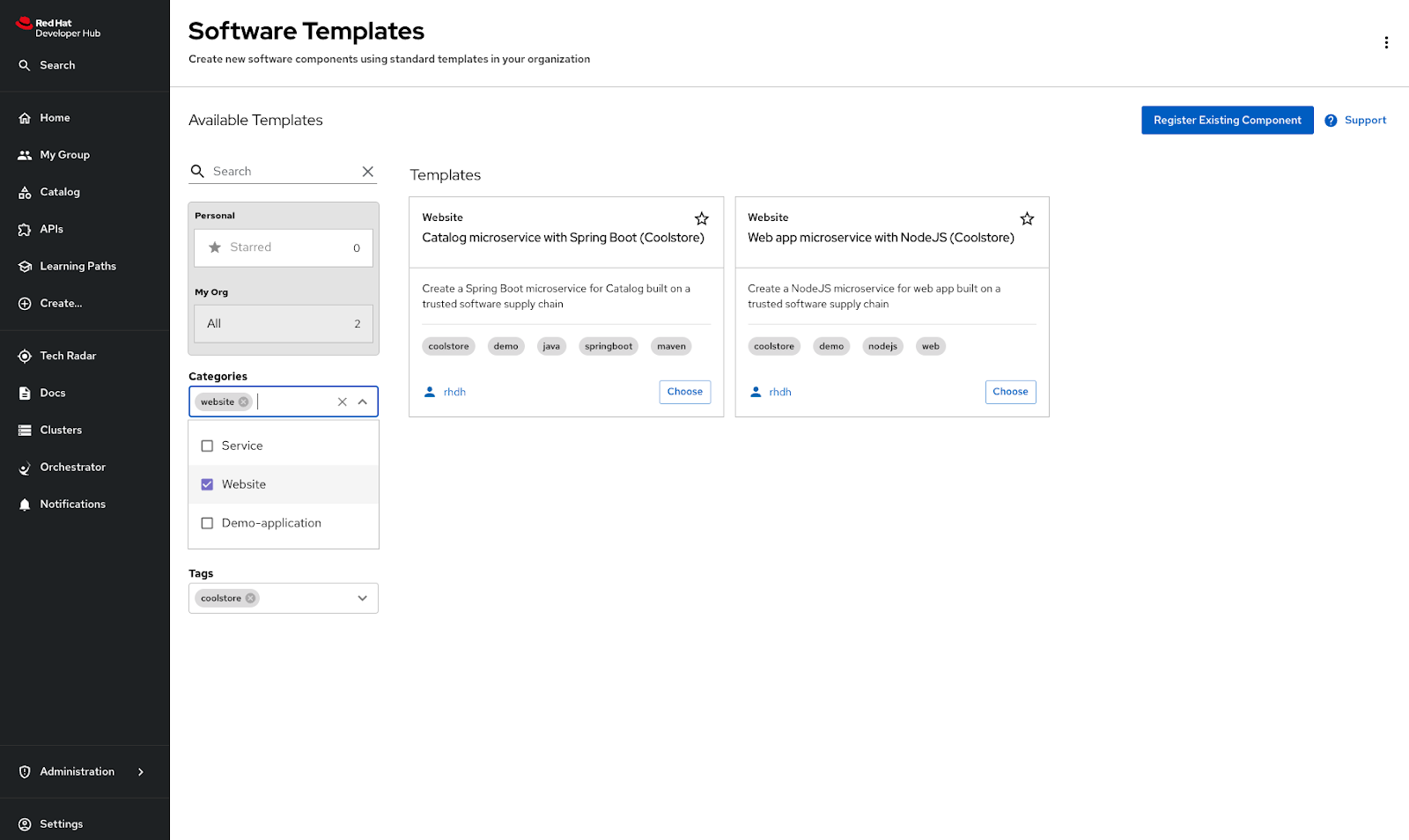

Tip #8: Specify the template type and tags

The Software Templates screen in Backstage lists all available templates by default. As you might imagine, this screen will become cluttered if you have multiple templates available.

Specifying a template’s spec.type is required, but most examples use the default value of service – thoughtfully set the type to organize templates in categories. Similarly, make use of metadata.tags to further classify templates into subcategories. Figure 7 shows a set of templates with a spec.type value of “website” and tagged as ”coolstore.”

Tip #9: Document your templates

Well-designed templates should be intuitive. Nevertheless, high-quality documentation makes self-service easier for developers with examples and an overview of what a template does. Figure 8 shows two templates: one with TechDocs enabled and one without.

Enabling a production-ready configuration for TechDocs on your Backstage or Red Hat Developer Hub instance requires object storage, but for the purpose of testing, you can use the following config:

techdocs:

builder: 'local'

publisher:

type: 'local'

generator:

runIn: localWith TechDocs enabled, add backstage.io/techdocs-ref annotation to the template.yaml, then create a mkdocs.yaml and a docs/index.md file relative to the template.yaml. A complete example is available in this GitHub repository.

Once everything is in place, you can view the TechDocs in your internal developer portal. Figure 9 shows an example.

Tip #10: Plan for maintenance

Software Templates open up exciting possibilities, but using them effectively requires a commitment to long-term support and maintenance.

Imagine a developer’s frustration if they scaffold a new application using your template only for it to immediately throw an error, or if they create a code that uses an outdated version of a key framework that contains critical security vulnerabilities that have since been patched.

Software Templates are supposed to codify your best practices and enhance developer productivity, so failure to keep your templates up to date will send the wrong message and undermine their value. Like regular software applications, you’ll need to update your templates to ensure they continue to work well. Be sure to avoid scaffolding code repositories with outdated code or dependencies.

An outdated template is a liability, not an asset. Plan to regularly update your software templates, and consider implementing automated tests using the scaffolder HTTP API endpoints to help you stay on top of things.

Bonus tip: How to accelerate the development loop

A local Backstage instance shrinks the feedback loop for template developers. You can deploy Red Hat Developer Hub locally using the open-source rhdh-local project. Alternatively, you can replicate a production-like deployment by using the Red Hat Developer Hub Operator or Red Hat Developer Hub Helm Chart on OpenShift Local.

Additionally, the quarkus-backstage extension simplifies the process of running Backstage locally with Gitea. It provides a DevUI, Dev Service, and a Backstage API client to simplify integration testing of your templates and other entities.

Wrap up

Software Templates and internal developer portals facilitate developer self-service, leading to happier and more productive development teams. Now that you’re equipped with my tips, you can craft experiences that empower your developers to innovate whilst following your organization’s best-practices. Get started with Red Hat Developer Hub on OpenShift to begin building your internal developer portal.