Zero trust architecture has become a modern security standard, built on the principle of "never trust, always verify." Unlike traditional perimeter-based security that assumes everything inside the network is trustworthy, zero trust requires continuous verification of every request, regardless of where it originates.

But for organizations with the highest security requirements (regulated industries, multi-tenant SaaS platforms, or environments processing sensitive data), there's a critical question: What happens when you can't fully trust the infrastructure itself? Traditional zero trust verifies who is calling, and what it's allowed to do, but it relies on the underlying infrastructure (Kubernetes, cloud platforms) being trustworthy.

This is where hardware-based security enters the picture. Red Hat OpenShift's sandboxed containers feature a new confidential containers feature that uses trusted execution environments (TEE) to create isolated, encrypted memory spaces (data in use) with cryptographic proof of integrity. These hardware guarantees mean workloads can prove they haven't been tampered with, and secrets can be protected, even from infrastructure administrators.

Red Hat's zero trust workload identity manager provides cryptographic workload identity, and is built on the SPIFFE/SPIRE open standards. Instead of services sharing static passwords or API keys that can be stolen or leaked, each workload receives a unique, automatically rotating cryptographic certificate (called an SVID). When one service calls another service, each proves its identity through cryptography, not shared secrets. This eliminates entire classes of credential theft and lateral movement attacks.

By integrating SPIRE with confidential containers, you get defense in depth: Cryptographic identity verification plus hardware rooted trust. Workload identity becomes anchored not just in software controls, but in the silicon itself. The result is a security architecture that protects against both network threats and infrastructure layer attacks.

In this article, we explore how these technologies work together, the security benefits they provide, and when this integration makes sense for your environment. In a future article, we'll provide hands-on guidance for deploying and configuring SPIRE with confidential containers in production.

Zero trust workload identity manager

Red Hat's zero trust workload identity manager provides centralized, scalable identity management across cloud platforms. Built on the SPIFFE/SPIRE open standards, it implements the "never trust, always verify" principle through continuous identity verification. SPIFFE serves as the universal identity standard (similar to how OAuth works for service identity), while SPIRE is the production-grade identity control plane that manages the actual servers and agents.

The core value proposition is simple: Replace static secrets with dynamic, short lived cryptographic identities called SVID (SPIFFE verifiable identity documents). In this article, we use the technical component names (SPIRE server, SPIRE agent, SVIDs), while understanding that they're all part of Red Hat's zero trust workload identity manager.

The paradigm shift: From secrets to identity

To understand why this matters, consider how services traditionally authenticate to each other.

The old way of communication, using shared secrets, looked like this:

- Service A needs to call Service B

- Store API key

- Inject the API key into Service A

- Service A sends API key along with its request

- Service B validates the API key

The challenge is that a key must be stored somewhere accessible, making it vulnerable to theft through configuration exposure, logs, or compromised infrastructure.

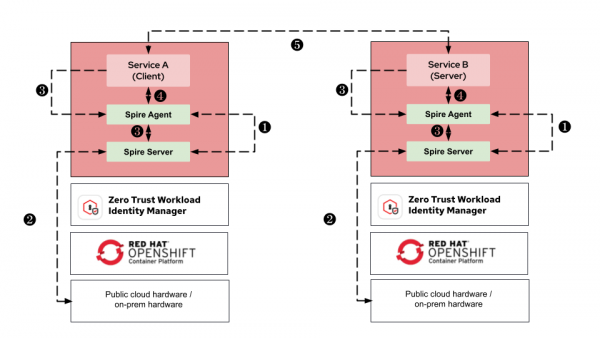

Figure 2 demonstrates the zero trust approach for service communication using a cryptographic identity:

In this model, when Service A needs to call Service B, both services obtain their identities:

- SPIRE agent starts node attestation by presenting platform credentials (Kubernetes service account token, cloud instance identity, or join token) to SPIRE server.

- SPIRE server validates the platform credentials and registers the agent as a trusted node in the trust domain.

- Workload requests identity from its local SPIRE agent, which attests the workload's properties (namespace, service account, process info) and forwards the request to SPIRE server.

- SPIRE server issues SVID to the workload through the authenticated agent, enabling the workload to perform mTLS with other services.

- Service A and Service B perform mTLS, each presenting their SVID. Both verify the other's certificate is signed by the trusted SPIRE CA and check the SPIFFE ID against authorization policy.

This approach can replace several traditional authentication mechanisms, such as API keys and internal service tokens, with short lived, automatically rotating SVIDs that enable mTLS between services.

Understanding SVIDs

An SVID (SPIFFE verifiable identity document) is a cryptographic document that proves a workload's identity. Think of it as a passport for your services. The most common type is an X.509 SVID, which is essentially a certificate containing:

- A SPIFFE ID (a URI like

spiffe://trust-domain/namespace/service-name) - A public key

- A signature from the SPIRE server (the certificate authority)

- A short expiration time (typically minutes or hours, not months or years)

When two services communicate using mTLS with SVIDs, they're performing mutual authentication. Both sides present their SVIDs, verify the signatures, verify that they're not expired, and confirm the SPIFFE IDs match the authorization policy. No shared secrets are needed.

How SPIRE establishes trust: A two-step process

SPIRE uses a two-step attestation process to issue SVIDs securely.

Step 1: Node attestation (agent identity)

Before any workload can get an identity, the SPIRE agent itself must prove its identity to the SPIRE server. This is called node attestation. The SPIRE agent runs on each node (physical server, VM, or Kubernetes node) and it needs to authenticate itself when it first starts up.

SPIRE supports multiple node attestation methods:

- k8s_psat: Uses Kubernetes projected service account tokens. The agent presents a token that Kubernetes signed, and the SPIRE server validates it against the Kubernetes API.

- Cloud instance identity: Uses cloud provider instance identity documents. The agent proves it's running on a specific computer instance.

- x509pop: Uses an x509 certificate. The agent presents a certificate signed by a trusted CA.

- join_token: Uses a pre-generated one-time token provided by an administrator.

Each method has different trust assumptions. For example, k8s_psat trusts that the Kubernetes API server correctly identifies nodes. AWS IID trusts the AWS infrastructure to provide authentic instance identity.

Step 2: Workload attestation (application identity)

Once the SPIRE agent is authenticated and running, it can start issuing SVIDs to workloads on its node. But first, it needs to identify which workload is making the request. This is called workload attestation. Common workload attestation methods include:

- Kubernetes: The agent identifies a workload by its Kubernetes namespace, service account, pod name, and other metadata.

- Unix: The agent identifies a workload by examining process information, like user ID, group ID, or even the SHA256 hash of the executable.

The SPIRE server has registration entries that map workload selectors (like Kubernetes namespace=payments, service account=payment-processor) to a SPIFFE ID. When a workload requests an SVID, the agent attests its properties, sends them to the server, and the server issues an SVID with the appropriate SPIFFE ID.

This two-step process creates a chain of trust. The infrastructure authenticates the agent, the agent authenticates the workload, and the workload gets a cryptographically signed identity it can use to authenticate to other services.

When infrastructure trust isn't enough

Traditional SPIRE deployments rely on infrastructure for trust. Node attestation methods, like k8s_psat trust Kubernetes to identify nodes correctly. AWS IID trusts the AWS platform. Join tokens trust that administrators distribute them securely.

For most organizations, this works fine. But that design does create attack vectors. Consider what happens if:

- Kubernetes API is compromised: An attacker with control over the Kubernetes API server could issue fake service account tokens, allowing them to register rogue SPIRE agents that can issue SVIDs to malicious workloads.

- Cloud provider is malicious or compromised: With cloud instance identity attestation, a compromised cloud provider could fake instance identity documents, allowing unauthorized agents to join the SPIRE trust domain.

- Infrastructure admin goes rogue: A malicious administrator with node access could inspect the memory of running SPIRE agents or workloads to extract private keys, SVIDs, or application secrets. SPIRE's cryptographic identities don't protect against physical memory inspection.

SPIRE excels at verifying who is calling, and safeguards against network-level attacks. However, its core assumption is a trustworthy infrastructure layer. When this assumption is challenged, hardware-rooted attestation becomes essential to extend the trust domain to potentially untrusted environments. This is where Red Hat's confidential containers comes into play

Confidential containers: Hardware-rooted trust

Red Hat's confidential containers use trusted execution environments (TEE), which are specialized CPU features that create isolated, encrypted memory spaces for workloads. Technologies like AMD SEV-SNP, Intel TDX, and Intel SGX provide hardware-enforced isolation where even privileged infrastructure operators cannot inspect workload memory or tamper with running code.

The key innovation is hardware attestation. When a workload starts in a TEE, the CPU generates a cryptographic measurement of exactly what code is running and in what environment. This measurement can be verified by remote parties to prove the workload is genuine and unmodified. Unlike platform-based attestation (which trusts Kubernetes or cloud APIs), TEE attestation is anchored in silicon and uses cryptographic proofs that are mathematically verifiable.

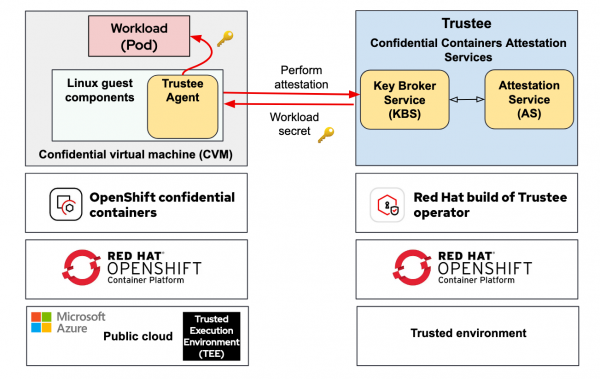

Figure 3 shows the overall confidential containers solution:

Confidential containers includes two main components: The runtime isolation layer (on the left side of figure 3) and the attestation and secret management layer (the right side in figure 3).

The runtime isolation layer uses Kata Containers to run each pod inside its own lightweight virtual machine (VM), providing VM-level isolation with a dedicated kernel and memory space. This isolation is what enables TEE protection.

The attestation and secret management layer, implemented through Trustee and the key broker service (KBS), ensures that only verified workloads can access sensitive information. Trustee validates that a pod is running inside a TEE. Once attestation succeeds, KBS securely provides the necessary secrets, such as encryption keys or credentials, to that verified pod.

For more information about confidential containers, read Exploring the OpenShift confidential containers solution.

How confidential containers address infrastructure attacks

Remember the attack scenarios from the previous section? Here's how confidential containers help.

Compromised Kubernetes or cloud provider

With TEE attestation, a fake service account token or instance identity document doesn't help an attacker. The integration works by using TEE attestation to establish hardware rooted trust for SPIRE agents. The workload attests to KBS using cryptographic measurements from the TEE. KBS validates the hardware evidence and releases bootstrap credentials (such as x509 certificates), and the SPIRE agent uses these hardware-attested credentials for node attestation. The agent's identity is ultimately anchored in silicon, not in a platform API. No amount of Kubernetes or cloud API control can fake the cryptographic evidence the CPU generates.

Rogue infrastructure admin

TEE memory encryption means even root users or hypervisor administrators cannot inspect workload memory to extract keys or secrets. The workload runs in a sealed environment that's cryptographically isolated from the host.

Combine zero trust identity with hardware attestation

When you integrate SPIRE with confidential containers, you create a complete trust chain from hardware to application identity. A common deployment pattern uses two clusters: A trusted cluster running the SPIRE server and Trustee (the control plane components), and a workload cluster running confidential containers. This separation ensures that even if the workload cluster is compromised, the core identity and attestation infrastructure remains protected.

The complete trust chain

The chain starts in silicon. The TEE hardware generates cryptographic measurements of the workload code and environment. Trustee validates these measurements and releases bootstrap credentials only to workloads that pass attestation. The SPIRE agent uses these hardware-attested credentials to authenticate with the SPIRE server. Once the agent is trusted, it can identify workloads running on its node and request SVIDs for them. Finally, workloads use their SVIDs for service-to-service authentication.

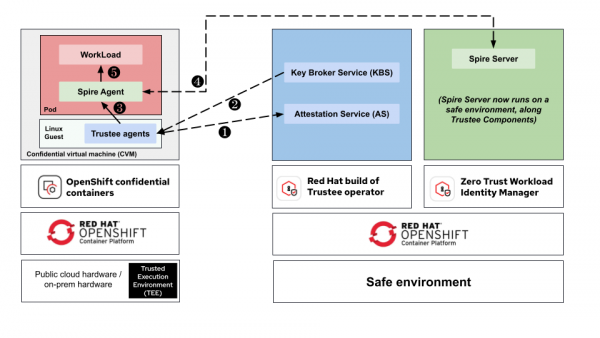

Figure 4 shows how SPIRE integrates with confidential containers, including the sequence of communication between different components:

- TEE evidence submission (Trustee agents to attestation service): The hardware root of trust (a TEE created by AMD SEV-SNP or Intel TDX) generates cryptographic measurements. The Trustee agent submits this evidence to the attestation service for validation.

- Bootstrap secret release (KBS to the Trustee agent): Only a genuine TEE passes attestation. KBS releases the bootstrap x509 certificate, dependent upon successful hardware verification.

- Credential delivery (Trustee agent to SPIRE agent): The hardware-attested certificate is delivered to the SPIRE agent. Identity is proven by silicon, not a platform API.

- Node attestation (SPIRE agent to SPIRE server): SPIRE agent authenticates to SPIRE server with x509pop, using the hardware-backed certificate. Agent identity is anchored in hardware.

- Workload identity (SPIRE agent to workload): After workload attestation, the SPIRE agent issues short-lived SVIDs. Workloads use these for service-to-service mTLS.

Each step builds on the previous one. Should any step fail (invalid TEE measurement, untrusted agent, unauthorized workload), the chain breaks and no identity is issued. This creates defense in depth, where trust flows from hardware through infrastructure to application identity.

Component roles

Here's a summary of the important terminology, and the role each component plays.

- Hardware (TEE): Generates cryptographic measurements, encrypts memory, produces attestation evidence that can be verified remotely.

- Trustee/KBS: Acts as the attestation authority. Validates TEE evidence and releases bootstrap credentials only to verified hardware.

- SPIRE agent: Runs on each node (or in each confidential workload). Uses hardware-attested credentials to authenticate with the SPIRE server. Identifies a workload and requests an SVID on its behalf.

- SPIRE server: The certificate authority for the trust domain. Issues SVIDs to workloads based on attestation from trusted agents.

- Workload: Receives an SVID with a SPIFFE ID, and uses it for mTLS connections to other services. The identity is ultimately backed by hardware attestation at the bottom of the chain.

The bootstrap problem and sealed secrets

There's a fundamental challenge in this architecture: How does the SPIRE agent get its initial bootstrap credentials (the x509 certificate and private key) to authenticate with the SPIRE server? You can't use traditional Kubernetes secrets because any cluster admin or attacker with etcd access can extract them. If the bootstrap credentials are exposed, an attacker can impersonate agents and break the entire trust chain.

This is where sealed secrets from the Confidential Containers project plays a key role. Instead of storing actual credentials in Kubernetes, you store references to secrets that live in KBS. These references can only be resolved inside a valid TEE after successful attestation. When a confidential pod starts, the confidential data hub (CDH) running inside the TEE performs attestation with KBS, proves the workload is genuine and unmodified, and only then receives the actual bootstrap credentials. The credentials never exist outside the TEE. They're not in etcd, not on the host, not in kubelet memory. They only materialize inside the encrypted memory of a verified hardware enclave.

This solves the bootstrap problem. Credentials are delivered securely to verified workloads without trusting the infrastructure to protect them.

Conclusion

TEE-backed zero trust makes sense when your threat model includes the infrastructure layer, when compliance requires hardware attestation, or when building multi-tenant systems where customers demand guarantees that other tenants can't access their data.

Confidential containers deliver strong binding for workload identity. Standard SPIRE node attestation methods (k8s_psat, AWS IID, join tokens) rely on infrastructure trust, compromise the platform and you can register rogue agents. Confidential containers allow credential release on TEE attestation: The hardware proves what code is running, KBS validates it, then releases the agent's x509 certificate inside encrypted memory. Even if a malicious actor were to steal the sealed secret from etcd, it's useless without the TEE.

For most deployments, standard SPIRE provides excellent security. But when you can't trust the platform, hardware-rooted identity is essential.

Last updated: January 8, 2026