Red Hat OpenShift networking is evolving to match the next generation of data center networking patterns. As data center fabrics transition toward transparent, standards-based architectures like BGP EVPN, OpenShift is moving beyond legacy isolation models. These improvements allow the platform to integrate seamlessly with the physical network, shifting from masquerading traffic behind node IPs to a "real routing" model.

By treating the cluster as a first-class member of the data center, we eliminate the complexity of double-NAT and asymmetric paths. This shift ensures that traffic maintains its workload identity, allowing firewalls and monitoring tools to function with full visibility. This article demonstrates how to achieve the following:

- Real routing: Assigning real, routable IPs to pods using cluster user defined networks (CUDN), eliminating node-level NAT entirely.

- Standards-based integration: Utilizing native free range routing (FRR) integration for dynamic BGP advertisements.

- Intelligent scoping: Balancing the use of CUDN for global corporate reachability versus UDN for strict tenant isolation and VRF-lite.

Solutions

The Kubernetes community has long explored ways to move past NAT-based patterns. Various alternatives (i.e., BGP-enabled CNIs, advanced eBPF dataplanes, and routing add-ons) were created to work around the legacy NAT models inherent in early container networking.

These efforts proved that better networking was possible, but they often required stitching together separate components outside the platform's core support. With the introduction of user defined networks (UDN) and BGP, standards-based routing is now a built-in capability of OpenShift. Enterprises can now deploy the Layer 3 (L3) networking they already run at scale directly within the cluster as a fully supported feature.

The toolkit CUDN and UDN

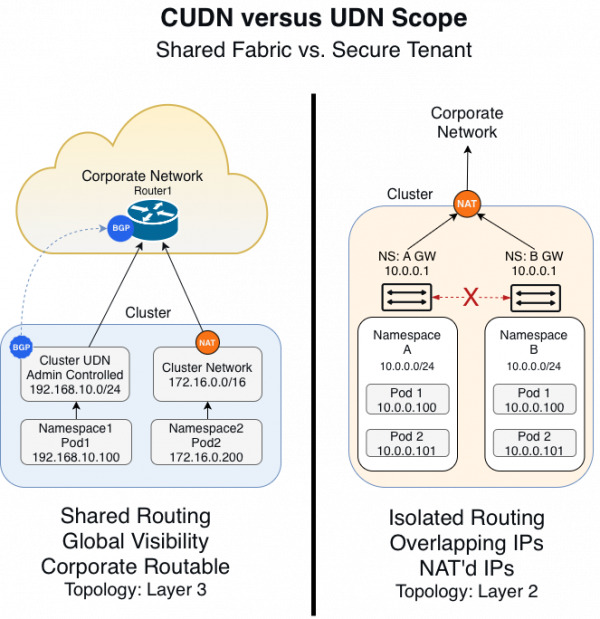

To implement this standards-based architecture, it is critical to use the right tool for the job. OpenShift 4.18+ uses two powerful custom resource definitions (CRDs) of networks with different scopes and purposes. Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of CUDN versus UDN.

CUDN: The fabric builder

Use the cluster user defined network (CUDN) as your primary tool for building a BGP-routed fabric. Because it is cluster-scoped, you only need to define your network once (i.e., a /16 Corporate Routable range), and the cluster automatically shares it across all projects.

The cluster carves this range into smaller subnets (like /24s) and assigns a unique block to each node. Your pods then receive real, routable IPs from these node-local blocks, replacing the default NAT'd overlay with direct Layer 3 connectivity.

Maintaining mobility in a routed world

Because CUDN ties IP addresses to specific node subnets, moving a virtual machine (VM) to a new node will change its physical IP. To ensure uptime during migrations, front your workloads with an OpenShift service or load balancer.

While this creates a double IP setup, it serves a strategic purpose. The service IP (identity) provides a stable, permanent front door for your users that never changes. The CUDN IP (performance) acts as a high-speed loading dock, allowing the network fabric to route traffic directly to the host via BGP without the CPU tax of NAT or the overhead of Geneve tunnels.

By separating identity from routing, you gain the agility to migrate workloads while leveraging the full power of a hardware-integrated network.

The power of primary

When you set the CUDN to role: Primary, you're doing more than just adding a second interface. You're upgrading the pod’s entire networking path. This configuration replaces the default OpenShift SDN, transforming eth0 from a hidden, NAT’d interface into a real, routable address directly on your corporate network.

UDN: The tenant isolator

Use the user defined network (UDN) when you need to enforce strict segmentation for your tenants. While a UDN supports routing, its true strength lies in providing precise Layer 2 (L2) topology control. By default, each UDN acts as a private island, preventing pods from communicating with other networks.

This isolation makes UDNs the perfect choice for the following scenarios:

- Multi-tenant hosting: Secure different teams or projects from one another effortlessly.

- Air-gapped testing: Build isolated environments that won't interfere with your production traffic.

- Overlapping IP ranges: Support multiple tenants using the same IP space (like

10.0.0.0/24) without causing conflicts.

By utilizing UDNs, you gain a foundational building block for advanced VRF-lite architectures, ensuring that sensitive data remains strictly separated at the network level.

The UDN is namespace-scoped, designed specifically for isolation. While you can use it for routing, its architectural superpower is segmentation and L2 topology control. By default, a UDN acts as a private island. Pods inside a UDN cannot communicate with pods in other UDNs, making it perfect for multi-tenant hosting, air-gapped testing environments, or overlapping IP ranges.

Use UDNs when a specific tenant (i.e., a dev team or a secure enclave) needs a custom network topology that the rest of the cluster shouldn't access. This is also the foundational building block for advanced VRF-lite architectures that require strictly separated routing tables.

Unlike the CUDN (which is typically Layer 3), you can configure a UDN with topology: Layer2. This allows you to bridge a specific namespace directly to a physical VLAN on the underlay network.

The Foundation of VRF-lite capability enables strict multi-tenancy. By mapping a UDN to a specific VLAN tag, you can extend a VRF (virtual routing and forwarding) instance from your top-of-rack switch directly into the namespace. This is the only way to support overlapping IP ranges (e.g., two tenants both using 10.0.0.0/24) without conflict.

Architectural warning: The hidden tax of VRF-lite

While VRF-lite is a powerful tool for isolation, you must be careful not to re-introduce the very problem we are trying to solve (NAT). When different tenants use the same IP addresses, they cannot reach shared services or the internet without an upstream firewall performing NAT on their traffic. This shift doesn't eliminate complexity; it simply moves the identity loss and management burden from the OpenShift node to your network edge.

To maintain a pure, real routing environment, you should default to CUDN for 90% of your workloads to ensure they stay NAT-free and fully visible. You should reserve the UDN and VRF-lite model strictly for specific tenants that require regulatory hard-separation or have unavoidable IP conflicts. By choosing CUDN as your standard, you minimize configuration sprawl and allow a single routing policy to cover hundreds of namespaces automatically.

The engine: Dynamic routing with FRR

Defining your networks is only the first step. To ensure your physical network can actually reach your pods, your infrastructure needs to know exactly where they live. In the past, this meant relying on fragile Layer 2 extensions or slow manual updates for static routes. OpenShift 4.18+ solves this by integrating free range routing (FRR) directly into the networking stack. This turns your cluster into a dynamic routing endpoint that speaks the native language of your data center (BGP).

Removing the need for a Geneve tunnel

To understand the value of this architecture, you must look at the packet level. In a standard cluster, cross-node traffic is hidden inside a Geneve tunnel. This default tunnel way wraps every packet in a 50-byte header, which forces you to lower your MTU size to prevent fragmentation. It also blinds your physical firewalls because they only see opaque UDP traffic between nodes rather than actual application flows.

By switching to a primary CUDN, you strip away this tunnel entirely. The pod's packet leaves the node interface without encapsulation, allowing you to use 1500-byte or jumbo frames. This change instantly increases throughput for data-heavy workloads and gives your operations teams deep visibility, as the source IP remains a real, routable address.

Eliminating the NAT tax for high-performance workloads

You can achieve your most significant performance gains by eliminating network address translation (NAT). In the legacy model, the Linux kernel rewrites every packet leaving a node to match the host node's IP. To ensure return traffic finds its way back, the system must maintain a massive connection tracking (conntrack) table. Under the heavy loads common in Telco or high-frequency trading, this table can reach its limit, causing conntrack exhaustion and resulting in dropped packets.

When you adopt stateless routing through CUDN and BGP, you remove this bottleneck entirely. Your nodes simply forward packets based on the destination IP without the need to rewrite headers or remember individual flows. This change drastically reduces CPU overhead on your nodes and eliminates the risk of conntrack exhaustion. By stripping away this NAT tax, you allow your cluster to push significantly higher packet-per-second (PPS) rates, ensuring your infrastructure stays ahead of your application's demands.

The routing lifecycle: A continuous sync with your fabric

With the tunnel and NAT removed, your cluster manages reachability through a continuous BGP loop. This process ensures the physical network always knows exactly where your workloads reside without manual intervention. By separating the service IP (identity) from the CUDN IP (location), you reconcile the need for seamless migration with the demand for high-performance routing.

When you launch a pod in a routable CUDN, the CNI assigns it a real, unique IP address from your pre-defined corporate block. Simultaneously, you assign an OpenShift Service or Load Balancer IP to act as the permanent "front door" for your application.

The FRR daemon on the host node immediately detects the new local workload. It automatically updates the node’s internal routing table, preparing it to handle traffic for that specific CUDN address.

Your node speaks directly to your Top-of-Rack (ToR) switch via BGP. It advertises the specific node-local route to the rest of the data center fabric.

If a workload moves to a different node, it receives a new CUDN IP from that new node's subnet. While the loading dock (CUDN IP) changes, the front door (service IP) stays the same. The fabric identifies the new path via BGP instantly, ensuring your users never lose their connection even as the routing table updates.

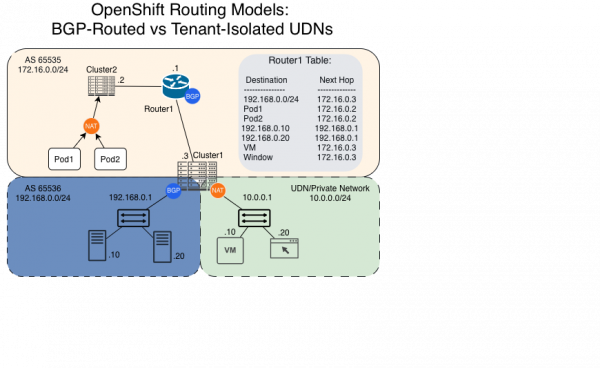

By automating this lifecycle, you move from a fragile, static environment to a resilient, routed architecture. This establishes a model of bidirectional trust. Your network team controls the BGP filters at the switch, while your cluster dynamically manages where the workloads actually run (Figure 2).

Layer 3 routing vs. Layer 2 extension

For network administrators, the choice between stretching Layer 2 (VLANs) and routing at Layer 3 is a pivotal decision for cluster stability. While extending VLANs across racks is a familiar way to ensure IP reachability, it expands your failure domain. A single broadcast storm or loop in one rack can cascade across your entire stretched segment, impacting unrelated workloads.

Beyond risk, you also face hard scaling limits. The IEEE 802.1Q standard limits you to 4,094 usable VLAN IDs, but your actual hardware—especially mid-range switches—often caps active VLANs much lower due to CPU and memory constraints. In a multi-tenant environment with thousands of namespaces, you will hit these bottlenecks quickly.

By adopting Layer 3 routing with CUDN and BGP, you can contain these failure domains. If a link or rack fails, BGP automatically identifies a new path, providing the reachability of a flat network with the resilience of a routed architecture. This approach simplifies your operations at scale and ensures faster network convergence. It also establishes a model of bidirectional trust. Your network team maintains control over what the cluster advertises via BGP filters, while the cluster dynamically manages where the workloads run.

The payoff: Unlocking your data center

Transitioning to BGP routing and eliminating NAT is about more than technical purity. It is about removing the artificial barriers between your applications and your data. This shift represents the maturity of the platform, providing identity-preserving, predictable routing for critical applications while maintaining the flexibility of private tenants.

Empowering application owners

Historically, connecting a container to a legacy system (i.e., a mainframe or a manufacturing controller) required you to build complex gateways. With CUDN, your pod receives a real, routable corporate IP address, enabling direct connections to databases and cloud services without proxies.

If you have applications that still require Layer 2 features like multicast or legacy clustering, you can use a UDN with Layer 2 topology. This configuration stitches your pod directly to an external VLAN, making the container appear as if it is physically plugged into the same switch as your legacy equipment.

Streamlining operations and security

In the old NAT model, your firewalls were blind. They only saw traffic originating from a worker node rather than the actual workload. This made it impossible to tell if a packet was a critical payment transaction or a developer’s test script.

By removing NAT, you provide your firewall with the real pod IP. Your security teams can now write granular rules, such as "Allow App A to talk to Database B," while your operations teams can use standard tools like ping or traceroute to debug connectivity issues instantly.

Standardizing the network fabric

When OpenShift speaks standard BGP, this is the key that unlocks your data center's most advanced capabilities. By advertising CUDN subnets as standard IP prefixes, your physical leaf switches can ingest and handle these routes according to your existing network policies.

Your cluster acts just like any other router in the rack, feeding routes into the fabric without requiring a specialized Kubernetes network. This prepares your infrastructure for future-ready segmentation like EVPN, where the fabric can place these routes into isolated virtual networks (L3VPNs) to maintain total security from the pod to the edge.

Setting the stage for the on-prem cloud

The integration of CUDN and BGP signals the maturity of the OpenShift platform. By choosing this architecture, you can provide identity-preserving, predictable routing for your critical applications while retaining the flexibility of UDNs for private tenants. You will no longer just manage a container platform; you will build a resilient network foundation that treats every workload as first class.

Real routing is just the beginning. Once you establish routable subnets and a BGP-integrated fabric, you will unlock the ability to run a true cloud model on-premises. In our next article, we will explore how to move toward abstracted networking, where you can use routable UDNs as virtual private clouds (VPCs) and leverage your EVPN fabric as a dynamic transit gateway. This shift transforms OpenShift from a simple orchestration tool into your organization’s internal cloud.