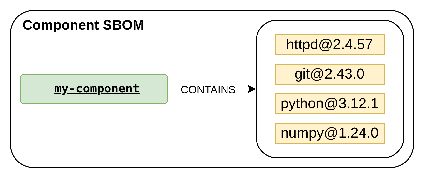

Common tools producing analyzed software bill of materials (SBOM) for container images provide a flat list of components (packages, libraries, RPMs, binaries) without indicating where each component originated. When a container image contains hundreds of packages, it can be hard to distinguish which ones came from parent images, builder stages, and those you installed directly.

At Red Hat, we're solving this problem by adding context to our SBOMs in an augmentation we call the contextual SBOM pattern. It addresses this issue by establishing relationships between container images and their parent (base images) and builder images within the software supply chain. Instead of treating each image as an isolated monolith, our contextual SBOM pattern has a hierarchical view showing how packages flow from parent to child images. The hierarchy in our implementation uses the relationships field and it's built on top of the SPDX 2.3 specification.

Understanding package provenance improves vulnerability management. When a CVE appears, you can immediately determine whether to update a parent image, update builder images, modify your Containerfile, or rethink the build process entirely. Our tooling to manage contextual SBOMs is still in active development, so this article focuses on a conceptual foundation: How a contextual SBOM pattern is structured. This includes information pertaining to its technical implementation (using SPDX 2.3 relationships), current limitations, and practical benefits for vulnerability management. A future article will cover the tooling ecosystem and provide step-by-step instructions for generating your own contextual SBOM.

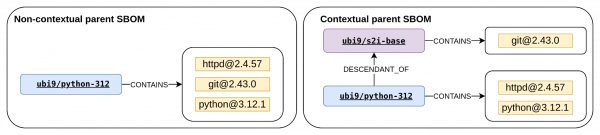

Traditional vs. contextual SBOM

SPDX specification uses relationships to describe connections between elements in an SBOM. The main difference between a traditional SBOM and the contextual SBOM patterns is that traditional SBOM generation tools create CONTAINS relationship types, but these only point an image's content to itself and also omit any references to parent or builder images. The contextual SBOM pattern uses the additional SPDX relationship types DESCENDANT_OF and BUILD_TOOL_OF to create relationships between the final image and its parent and builder images. It then uses CONTAINS relationships to express the true origin of contained packages, whether they come from a parent image, builder images, or were directly installed in the final image.

The contextual SBOM pattern in vulnerability management

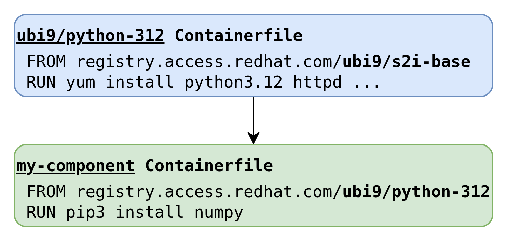

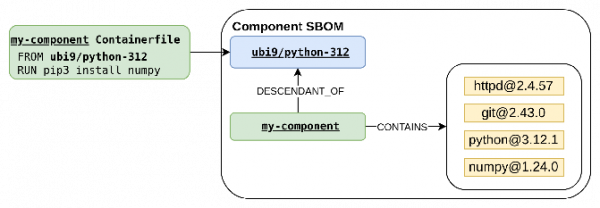

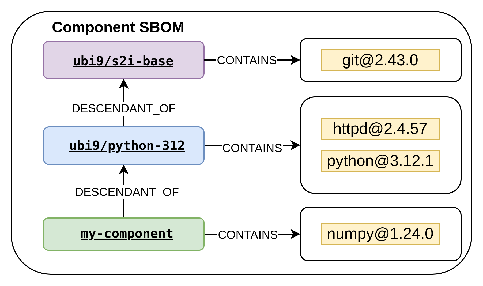

Consider a practical example. Suppose you've built a custom application on top of the ubi9/python-312 parent. This simplified two-level image chain in Figure 1 demonstrates how the contextual SBOM pattern is helpful in vulnerability management.

The traditional SBOM generated from the final my-component image shows my-component CONTAINS numpy and my-component CONTAINS httpd. Although these statements are true, they do not provide any provenance information. This absence of package origin attribution prevents effective vulnerability management.

Use case 1: Parent image vulnerability remediation

Suppose a critical vulnerability has been discovered in the httpd package. Your component image was built using the my-component Containerfile shown in Figure 1, and your component image SBOM shows that this package is present. With a traditional SBOM, you might assume you need to update your Containerfile and rebuild. However, the contextual SBOM reveals the following:

ubi9/python-312 CONTAINS httpd@2.4.57ubi9/python-312 CONTAINS python@3.12.1my-component CONTAINS numpymy-component DESCENDANT_OF ubi9/python-312

This immediately reveals that the vulnerability originates from the parent image ubi9/python-312 and not from your component's direct installations. Your remediation path might look like this:

- Acknowledge the Red Hat UBI team and wait for the

ubi9/python-312release with the patchedhttpdpackage. - Rebuild your component image to inherit the fix.

No my-component Containerfile httpd package updates are required.

Without this context, you could spend extra time investigating your build process or attempting to override the package manually, which could potentially create maintenance issues. In contrast, if a vulnerability is identified in a numpy package installed in the Containerfile, a contextual SBOM helps you quickly understand that updating it is your action item.

Builder image content

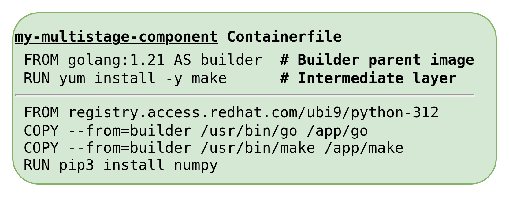

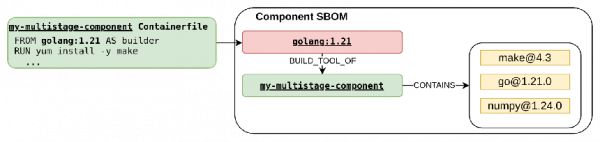

Multistage builds introduce a third content source: Builder stages. Here's a simple multistage build example to demonstrate how we enrich a contextual SBOM for builder content.

In this example:

- Builder parent image:

golang:1.21contains thegobinary. - Intermediate layer: Created after

RUN yum install -y makeand adds themakepackage. - Final component: Copies

gofrom builder parent andmakefrom the intermediate layer, then installsnumpydirectly.

Builder content is neither sourced from the parent image or explicitly installed in the component's final layer. It is copied from builder stages with COPY instructions.

Builder content can originate from two places, and this origin plays a major role in vulnerability management:

- Builder stage parent image: Should a vulnerable package come from the builder parent image (for example,

golang:1.21), the builder parent image must be updated and then your component must be rebuilt. - Intermediate layer installations: If a package was installed in an intermediate build stage and then copied, then your Containerfile (NOT the builder parent image) must be updated.

Correctly distinguishing between these two sources is critical for efficient remediation.

Use case 2: Builder stage vulnerability remediation

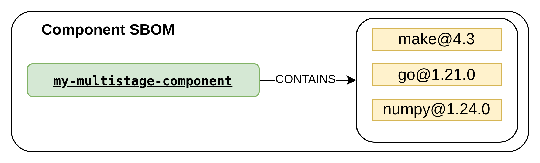

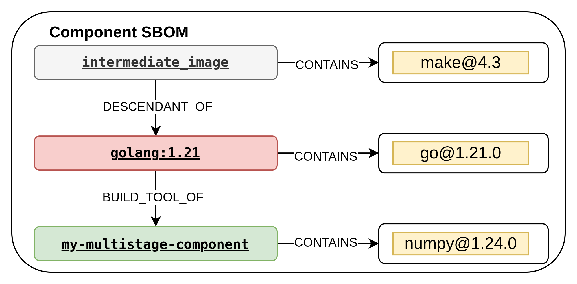

Suppose a critical vulnerability is discovered, affecting the go binary version 1.21.0. Your component image is a product of the multistage build from Containerfile shown in Figure 2. A traditional SBOM would show:

my-multistage-component CONTAINS go@1.21.0my-multistage-component CONTAINS make@4.3my-multistage-component CONTAINS numpy@1.24.0

This provides no indication of where go originated, leading to unclear remediation steps. However, your contextual SBOM reveals true provenance:

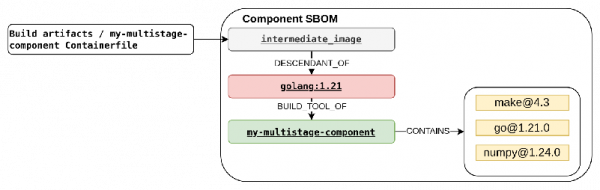

golang:1.21 BUILD_TOOL_OF my-multistage-componentbuilder-intermediate DESCENDANT_OF golang:1.21golang:1.21 CONTAINS go@1.21.0builder-intermediate CONTAINS make@4.3my-component CONTAINS numpy@1.24.0

This clearly shows that go originated from the golang:1.21 builder parent image. Your remediation path might look like this:

- Builder image owner or maintainer must fix the Go version in the builder image.

- The builder parent image must be updated in your Containerfile from

golang:1.21to a patched version (for example,golang:1.22). - The component image must be rebuilt to inherit the fixed go binary.

There are no changes to your COPY instructions or installation commands required. The vulnerability is inherited from the updated builder parent image, so updating that image resolves the issue. The contextual SBOM helps you make the right decision immediately.

In contrast, if a vulnerability appeared in make@4.3, installed in the intermediate layer using RUN yum install -y make, then the contextual SBOM would show builder-intermediate CONTAINS make@4.3, indicating that you must update your Containerfile. From a remediation perspective, content installed in an intermediate builder layer requires the same action as content installed in the final layer (like numpy@1.24.0 in these examples). Both are your responsibility to maintain and update.

How to create a contextual SBOM

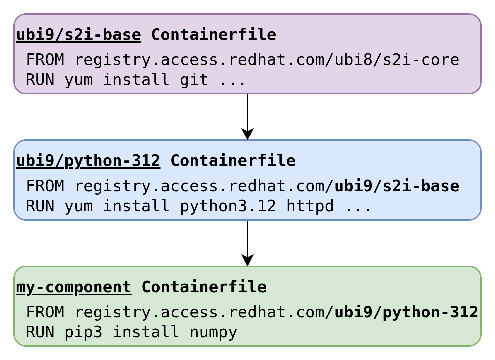

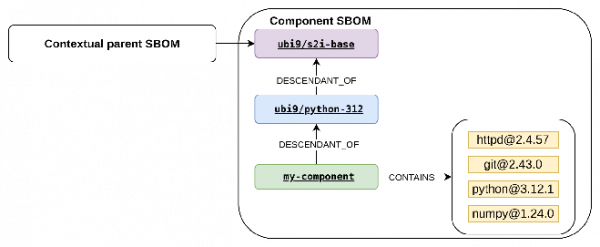

To demonstrate the difference between content sourced from a parent image and content installed during a build, consider Figure 1 extended into a three-level image chain, as shown in Figure 2, which captures the ancestor of the ubi9/python-312 - ubi9/s2i-base image.

The transformation of a traditional SBOM produced from a built component into a contextual SBOM:

1. Generation of the component SBOM

To begin with, we produce a non-contextual traditional SBOM (in SPDX format) from our component image. In the following steps, we'll transform it into a contextual SBOM pattern.

2. Obtaining the parent SBOM

This is the component's parent image SBOM. The next steps will transform the component's traditional SBOM from the previous step into a contextual SBOM pattern.

We could potentially generate this parent SBOM from build artifacts. The build process typically preserves the parent image. However, generating just another traditional SBOM may discard valuable information, as shown in Figure 5.

If we are also in control of SBOM generation for the ubi9/python-312 parent image, its repository may already contain a contextual SBOM, as shown in Figure 5. This SBOM may contain relationships to its own parent, the grandparent of your component, such as ubi9/s2i-base.

This important concept is how the contextual SBOM pattern accumulates provenance information across the entire build chain. If your build ecosystem is layered and your images serve as bases for other products, the design of the contextual SBOM pattern encourages downloading the parent SBOM from the repository to preserve the complete ancestry. In later steps, we'll work with the contextualized parent SBOM to demonstrate the full ability of the contextual SBOM pattern.

3. Setting up the parent-child relationship

Now we can start with the modification of the component's traditional SBOM. First, add a package entry to the component SBOM that describes the ubi9/python-312 parent image. This information can be accessed from Containerfile. Then establish the parent-child relationship using the SPDX DESCENDANT_OF relationship type: my-component DESCENDANT_OF ubi9/python-312. The component SBOM is now expressing a relationship with its parent image, as in Figure 6.

4. Copying parent-child relationships from parent

If the parent SBOM is already a contextual SBOM, then the package of its parent (ubi9/s2i-base) must be present, and we need to copy this package describing ubi9/s2i-base, the parent of ubi9/python-312, and the relationship ubi9/python-312 DESCENDANT_OF ubi9/s2i-base to the component image SBOM. If there are more ancestor records, then we add them the same way.

The Component SBOM acquires information about all known image ancestors.

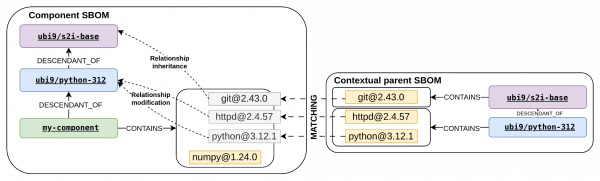

5. Update package relationships in the component SBOM

Now it's time to differentiate between content of the parent and component. This process consists of matching packages between parent and component and updating relationships in the component. We do this by matching packages from the parent image SBOM against packages in the component image SBOM. When the same package appears in both the parent and component SBOM, it is considered to have originated from the parent image. For each matched package, we update the relationship to reflect its true origin.

For httpd installed in python-312, we modify component CONTAINS httpd to python-312 CONTAINS httpd.

For git installed in s2i-base, we change component CONTAINS git to s2i-base CONTAINS git by inheriting it from the parent SBOM. To set this relationship accurately, the SBOM of ubi9/python-312 must be contextualized. This relationship is then inherited from the parent SBOM. Otherwise, this package's relationship will be modified as python-312 CONTAINS git.

Any unmatched package not found in the parent image is considered to be content you installed directly, such as component CONTAINS numpy.

- Packages found in the component image but not in the parent image represent content you installed directly in the Containerfile.

- Packages present in the parent image that don't appear in the component image were either explicitly deleted during the build by Containerfile instructions, or removed or updated by package managers as dependencies during the build.

- The parent image SBOM is a snapshot at build time. When used as a parent, its filesystem may change during the descendant build. Unmatched parent packages indicate content removed during build time. This doesn't affect the final SBOM, but informs changes occurring between parent and child images.

At this point, our component SBOM has been fully transformed to the contextual SBOM pattern. Figure 9 summarizes all changes made.

We cannot always count on the presence of the contextual SBOM in the parent's repository. If the downloaded parent SBOM is not contextual (see Figure 4, on the left), then we can still set up the parent package and DESCENDANT_OF relationship with a component, and track the component's packages up to this parent. If no parent SBOM exists in the registry, then we can generate it locally and execute the same process.

At this point, your contextual SBOM correctly tracks its identifiable ancestor images and differentiates between content installed in the component image and content sourced from parent images. However, two technical challenges remain.

Limitations of package matching

Matching packages between different SPDX documents requires consistent unique identifiers. However, the SPDX specification does not enforce any per-package unique identifier. Still, SBOM generation tools may optionally inject three unique identifiers into SPDX packages:

- Checksums: If parent and component SBOMs use the same checksum algorithm and calculation approach, then we can use checksums for package comparison.

- Package verification code: The SPDX specification states that this field "provides an independently reproducible mechanism identifying specific contents of a package based on the actual files." Therefore, this identifier is also suitable for matching packages between different SPDX documents.

- Purl: A package URL may serve as unique identifiers when they include sufficient detail. The purl specification requires only the type (such as pypi, npm, or gem) and name (such as

curlordjango), which is insufficient for unique identification. However, when version and optionally namespace are included, purl promotes a reliable unique identifier for package comparison across SPDX documents.

For example, these purls include type, the namespace redhat, name, and version, which makes them suitable for unique package identification:

pkg:pypi/numpy@1.24.0

pkg:rpm/redhat/httpd@2.4.57-8.el9The problem is that some packages, including various files and custom binaries, contain no such unique identifier. There is no reliable method for matching these packages between documents, so you cannot mark their source. When you find such a package in your component SBOM, you know it exists in your component but cannot determine its origin.

In a trusted ecosystem where every package requires auditability, two questions emerge at two different points in the process:

Before SBOM generation

- Is your SBOM generation tool specific enough for your purposes?

- Can you improve it or should you use a different tool?

After SBOM analysis

- Should you pay closer attention to packages without identifiers?

- Should you eliminate such packages from your products?

These questions extend beyond contextual SBOM pattern capabilities, but contextual SBOM pattern exposes these gaps and enables improvements in SBOM generation and vulnerability prevention.

Builder content identification

For builder content resolution, a different approach must be used. In the case of a multistage build, the parent content identification process described earlier leaves this builder content appearing as if it were installed directly in the component image.

Downloading or generating SBOMs for every builder stage parent image, generating intermediate layer SBOM, and matching packages between them to find out every package's origin is resource-intensive. Moreover, builder stages may use third-party parent images that has no SBOM, or the SBOM may be very large or improperly formatted. Instead, we developed a targeted approach, and our contextual SBOM pattern identifies builder content through Containerfile and build artifacts analysis, looking at images used in the build process. For the demonstration of the builder content identification, we use the Containerfile displayed in Figure 1. The first step is the identification, and determination of the origin, of the builder content:

- Extract COPY instruction metadata: Parse the Containerfile to collect builder names (aliases), source paths, and destination paths from COPY instructions. For example,

COPY --from=builder source destination. - Identify builder images: Based on builder names or aliases, select the corresponding builder parent images and any corresponding intermediate images created during the build. This approach requires the build system to preserve builder stage parent images and intermediate images from each stage.

- Explore content in builder images: Map source paths to the original builder parent images and intermediate images to determine which packages exist at those paths, determining if these packages are sourced directly from the builder parent image or have been later installed in the intermediate layer, and perform a partial SBOM scan. The result is a set of small SBOMs for each stage containing only the packages copied into the final component image.

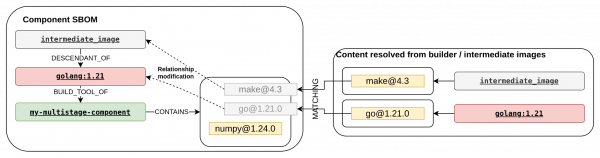

The second step is the translation of the resolved builder content into component SBOM, as in Figure 10.

For simplicity, this and following examples neglect parent content identification.

Builder parent images: Use information from the parsed Containerfile, and create a package entry for each builder parent image and establish the relationship:

builder BUILD_TOOL_OF component(Figure 11). The component SBOM is now aware of the builder parent images used.

Figure 11: Added package and relationship indicating builder parent image of our component. Intermediate images: Create a package entry for each intermediate image and establish the relationship:

intermediate_image DESCENDANT_OF builder(see Figure 12) connecting it with its builder parent image. Information about intermediate images is derived from the parsed Containerfile and present build artifacts. Component SBOM is now fully describing image flow during multistage build.

Figure 12: Added package and relationship indicating intermediate parent image of our component. - Package origin updates: Map packages from the builder content SBOMs to packages previously marked as component-installed. Update relationships to reflect true origin (see Figure 13).

component CONTAINS go→golang:1.21 CONTAINS gocomponent CONTAINS make→intermediate_image CONTAINS make

Figure 14 summarizes all changes made.

This example shows:

- Builder parent image:

golang:1.21is declared as a package and linked to the component using theBUILD_TOOL_OFrelationship, indicating that this entire builder image serves as a build tool for the final image. - Intermediate image:

intermediate-imageis declared as a package and linked togolang:1.21using theDESCENDANT_OFrelationship, indicating that this intermediate image descends from the builder parent image. - Package origins are now correct:

gofrom the builder parent,makefrom the intermediate layer, andnumpyfrom the component.

At this point, the content is fully contextualized from the perspective of a multistage build, and your contextual SBOM is ready for vulnerability management.

Conclusion

The contextual SBOM pattern applied at build time transforms flat package lists into hierarchical provenance chains, enabling faster and more accurate vulnerability remediation. By distinguishing between content from parent images, builder stages, and direct installations, you can immediately identify which component to update when a CVE appears. While limitations to package matching exist due to inconsistent identifiers, a contextual SBOM pattern exposes these gaps and drives improvements in SBOM generation practices. As container build ecosystems become more complex, understanding package provenance is essential for effective security, especially efficient vulnerability management.

For contextual SBOM pattern implementation or improvement suggestions, message us in the konflux-ci community slack instance.

If you want to learn more about software provenance, check out the article How we use software provenance at Red Hat.