"I used WildFly Swarm to shrink my app from 45 megabytes to only 2243 bytes."

I was recently playing around with various techniques for packaging Java microservices and running on OpenShift using various runtimes and frameworks to illustrate their differences (WildFly Swarm vs. WildFly, Spring Boot vs. the world, etc). Around the same time as I was doing this an internal email list thread ignited discussing some of the differences and using terms like Uber JARs, Thin WARs, Skinny WARs, and a few others. Some folks were highlighting the pros and cons of each, especially the benefits of the thin WAR approach when combined with docker image layers.

And I thought to myself: isn’t this what everyone is already doing? Do developers really have to think about this stuff? But before I get into that, I want to define the various terms I’ve heard and at least get it straight in my own head.

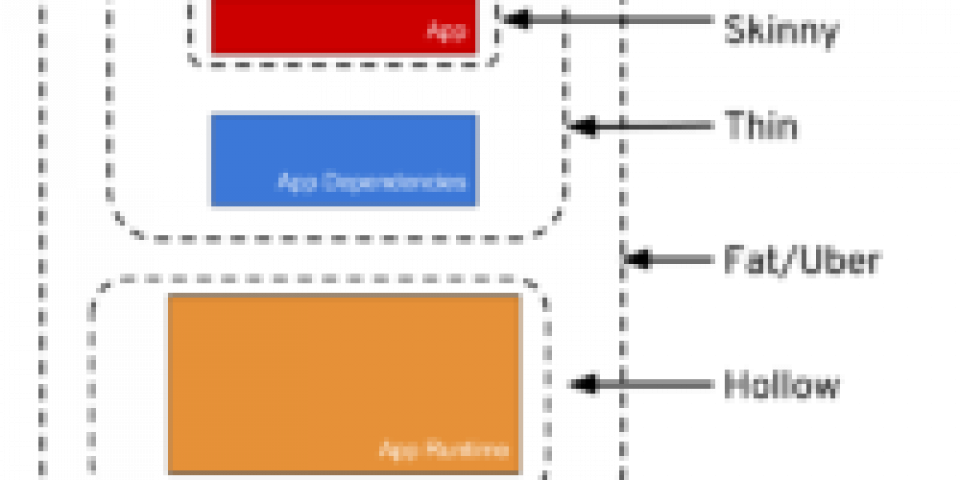

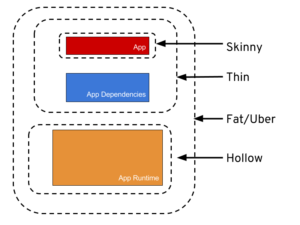

The Qualifiers (in increasing order of logical size)

- Skinny - Contains ONLY the bits you literally type into your code editor, and NOTHING else.

- Thin - Contains all of the above PLUS the app’s direct dependencies of your app (db drivers, utility libraries, etc).

- Hollow - The inverse of Thin - Contains only the bits needed to run your app but does NOT contain the app itself. Basically a pre-packaged “app server” to which you can later deploy your app, in the same style as traditional Java EE app servers, but with important differences, we’ll get to later.

- Fat/Uber - Contains the bit you literally write yourself PLUS the direct dependencies of your app PLUS the bits needed to run your app “on its own”.

Now let’s define how the qualifiers map to the world of Java applications and package types (JAR, WAR, etc).

Fat/Uber JAR

Maven and in particular Spring Boot popularized this well-known approach to packaging, which includes everything needed to run the whole app on a standard Java Runtime environment (i.e. so you can run the app with java -jar myapp.jar). The amount of extra runtime stuff included in the Uberjar (and its file size) depends on the framework and runtime features your app uses.

Thin WAR

If you’re a Java EE developer, chances are you’re already doing this. It is what you have been doing for over a decade, so congratulations you’re still cool! A thin WAR is a Java EE web application that only contains the web content and business logic you wrote, along with 3rd-party dependencies. It does not contain anything provided by the Java EE runtime, hence it’s "thin" but it cannot run "on its own" - it must be deployed to a Java EE app server or Servlet container that contains the "last mile" of bits needed to run the app on the JVM.

Thin JAR

Same as a Thin WAR, except using the JAR packaging format. Typically, this is used by specialized applications/plugin architectures that use the JAR packaging format for its purpose-built plugin or runtime artifacts. For example, the .kjar format from Drools.

Skinny WAR

While less well known than its brethren, a skinny WAR is thinner than a Thin WAR because it does not include any of the 3rd-party libraries that the app depends on. It ONLY contains the (byte) code that you as the developer literally type in your editor. This makes a lot of sense in the docker world of layered container images, where layer size is important for DevOps sanity, and Adam Bien has done an awesome job demonstrating and explaining this. More on this later.

Skinny JAR

The same as a Skinny WAR, except using JAR packaging and frameworks built around it such as WildFly Swarm and Spring Boot. This also makes a ton of sense for CI/CD sanity (and your AWS bill) - just ask Hubspot. Here you take a Thin WAR and remove all the 3rd-party dependencies. You’re left with the smallest atomic unit of app (attempting to go smaller sounds like a terrible idea but with Java 9/JPMS is might be possible), and it must be deployed to a runtime that is expecting it AND has all of the other needed bits to run the app (such as a Hollow JAR)

Hollow JAR

This is a Java application runtime that contains “just enough” app server to run applications but does not contain any applications itself. It can run on its own but isn’t that useful when running on its own since it doesn’t contain applications and won’t do anything other than initializing itself. Some projects like WildFly Swarm allow you to customize how much is “just enough” while others (like Paraya Micro, or TomEE) provide pre-built distributions of popular combinations of runtime components, such as those defined by Eclipse MicroProfile.

The other combinations

- Hollow WAR - In theory you could package some kind app to run within another app server and then deploy apps to that inner layer. Good luck with that!

- Fat/Uber WAR - Doesn’t make sense with the general idea of Fat/Ubers being runnable with java-jar.

- EAR files - by definition an EAR file cannot be hollow, fat, or skinny, so all you can create is a Thin EAR (which is what it is already, by definition). Move along, nothing to see here, except that EAR files could be the vehicle that carries dependencies for skinny WARs within the EAR.

Why bother?

The rise of for-rent computing and the popularity of devops processes, Linux containers, and microservice architectures has made app footprint (the number of bytes that make up your app) important again. When you’re deploying to dev, test, and production environments multiple times a day (sometimes hundreds per hour or even 2 billion times a week), minimizing the size of your app can have a huge impact on overall devops efficiency, and your operational sanity. You don’t have to minimize the lines of code in your app, but you should reduce the number of times your app and its app dependencies have to pass across a network, move onto or off of a disk, or be processed by a program. That means breaking your app into different packaged parts so that they can be properly separated and treated as such (and even versioned if you so choose).

With cloud native microservices, this means using layered Linux container images. If you can separate your app’s components into different layers, putting the most frequently changing parts of your app on “top” and the least frequently changing parts on the “bottom”, then every time you re-construct a new version of your app you are in reality only touching the highest levels. Saving time across the board for storage, transport, and processing of the new version of your app.

Great. Just tell me which one to use!

It depends. The pros/cons of each have been discussed by others [here, here and here]. Fat/Uber JARs are attractive due to their portability, ease of execution in IDEs and its all-you-need-is-a-JRE characteristic. But the more you can separate the layers (into skinny/thin), the more you will save on network/disk/cpu further down the line. There’s also the added benefit of being able to patch all the layers independently, for example, to subscribe and quickly distribute fixes for security vulnerabilities to all of your running apps). So, you have to decide amongst the tradeoffs.

Example: WildFly Swarm

WildFly Swarm is a mechanism for packaging Java applications that contain “just enough” functionality to run the app. It has an abstraction called a Fraction, each of which embodies some functionality that apps need. You can select which Fractions you need, and package only those fractions along with your app to produce a minimized and specialized runnable image for your app.

WildFly Swarm has the ability to create many of the above types of packaged apps. Let’s look at what it can do and the resulting size(s) of various packaging options, and how it applies in the world of layered Linux container images. We’ll start with the Fat/Uber JAR and work our way down. Grab the code and follow along:

$ git clone https://github.com/jamesfalkner/wfswarm-packaging-demo

Fat/Uber JARs

The sample app is a simple JAX-RS endpoint that returns a message. It has one direct dependency on Joda Time, which we’ll use later on. For now, let’s make a Fat JAR (which is the default mode of WildFly Swarm) using the code in the fat-thin/ folder:

$ cd fat-thin; mvn clean package $ du -hs target/*.jar 45M target/weight-1.0-swarm.jar

You can test it out with java -jar target/weight-1.0-swarm.jar and then curl http://localhost:8080/api/hello in a separate terminal window.

Not bad - 45M in size for a completely self-contained FAT jar. You could stuff this in a docker image layer everytime you rebuild, but that 45M will grow as you actually implement a real-world app. Let’s see if we can do better.

Thin WARs

As part of the above build of the Fat JAR, WildFly Swarm also created a Thin WAR so no rebuild is necessary. Take a look at the Thin WAR:

$ du -hs target/*.war 512K target/weight-1.0.war

Now we’re getting somewhere. This 512K Thin WAR could be deployed to any app server (such as WildFly itself). So if you stuff this much smaller file into your upper docker layers while your rarely-changed app server lives in a lower layer (as Adam Bien demos multiple times), you’ll save quite a bit of time and energy during multiple builds. Let’s keep going.

Skinny WARs

You may have noticed in the demo app that it’s super-simple - only a few lines of code. So why does it take 512K to hold it? Most of the 512M in the Thin WAR is taken up by our direct dependencies - in this case, the Joda Time library:

% unzip -l target/*.war Archive: target/weight-1.0.war Length Date Time Name -------- ---- ---- ---- 0 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/ 134 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/com/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/lib/ 746 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/HelloEndpoint.class 402 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/RestApplication.class 634048 08-03-17 01:14 WEB-INF/lib/joda-time-2.9.9.jar <------ This one 0 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/maven/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/maven/com.test/ 0 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/maven/com.test/weight/ 2954 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/maven/com.test/weight/pom.xml 97 08-03-17 01:14 META-INF/maven/com.test/weight/pom.properties -------- ------- 638381 16 files

If we continue to add direct dependencies (like database drivers and other things virtually every production app will need), our Thin WAR will also grow and grow in size over time. While 512K isn’t bad, we can do much better.

Skinny WAR: Removing direct dependencies

With Maven you could remove the direct dependency from the resulting Thin WAR by declaring it has to be provided, meaning that the runtime (in this case, WildFly) is expected to provide that dependency. Due to the nature of app servers and WildFly’s modular class loader, to make WildFly provide this dependency when your app is deployed to it you would need to create a custom JBoss Module definition in your Wildfly configuration and declare a dependency on that module in your app.

WildFly Swarm provides a better way that does not require that you touch the app server bits at all. We can create a custom module called a Fraction. Fractions are first-class citizens in WildFly Swarm, and it has special logic which links code inside of Fractions with application code at runtime. By doing this, our application truly has no dependencies and becomes a Skinny WAR.

I’ve created a fraction to house the Joda Time library in the joda-fraction/ folder within the example app’s source. Let’s build it and copy it to our Maven repo for later referencing:

$ cd joda-fraction; mvn clean package install [INFO] --- maven-install-plugin:2.4:install (default-install) @ joda --- [INFO] Installing /Users/jfalkner/ws/fat/joda-fraction/target/joda-1.2.jar to /Users/jfalkner/.m2/repository/com/jhf/joda/1.2/joda-1.2.jar [INFO] Installing /Users/jfalkner/ws/fat/joda-fraction/pom.xml to /Users/jfalkner/.m2/repository/com/jhf/joda/1.2/joda-1.2.pom [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ [INFO] BUILD SUCCESS [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now that the fraction is built, rebuild the skinny version of the app (in the skinny/ folder):

$ cd ../skinny; mvn clean package $ ls -l target/*.war -rw-r--r-- 1 jfalkner staff 2243 Aug 3 01:45 target/weight-1.0.war

Now we’re getting somewhere! Our Skinny WAR is 2243 bytes. That’s as small as it gets, as it literally only contains our code:

$ unzip -l target/*.war Archive: target/weight-1.0.war Length Date Time Name -------- ---- ---- ---- 99 08-03-17 01:45 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF 0 08-03-17 01:45 META-INF/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/com/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/ 0 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/lib/ 402 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/RestApplication.class 746 08-03-17 01:45 WEB-INF/classes/com/test/rest/HelloEndpoint.class -------- ------- 1247 10 files

It’s completely unusable on its own, however. It requires not only an app server with JAX-RS support but also a server that can provide our direct Joda Time dependency. WildFly Swarm provides another facility to create such a server runtime that will contain just enough app server PLUS our newly separated Joda Time dependency. It’s called a Hollow JAR.

Hollow JARs

To build a hollow JAR suitable for running our sample app, we can use a WildFly Swarm property to instruct the Maven plugin to build it:

$ mvn clean package -Dswarm.hollow=true $ du -hs target/*.jar target/*.war 44M target/weight-1.0-hollow-swarm.jar 4.0K target/weight-1.0.war

There’s the hollow server weighing in at 44M and our skinny WAR at 2243 bytes (the Linux du utility reports disk space allocated in units of the filesystem’s block size, which is 4K on my system, but rest assured the skinny WAR is indeed 2243 bytes and when transferred over a network only 2243 bytes will be sent).

Now you can stuff the hollow JAR into a Linux container layer, and then stuff the skinny WAR on top. When you rebuild your project with new code, assuming you’re not adding more dependencies to the app server, only your skinny WAR will be rebuilt, saving time, disk space, trees, and your sanity during those 2 billion container rebuilds you do each week.

To run your skinny app and verify it still works in conjunction with the hollow server you’ve just created:

$ java -jar target/weight-1.0-hollow-swarm.jar target/weight-1.0.war

And in another terminal:

$ curl http://localhost:8080/api/hello hello, the date is 2017-08-03

What about Spring Boot?

Spring Boot’s out of the box defaults are also to build a fat jar, so let’s have a look at the example Boot app:

$ cd spring-boot-fat; mvn clean package $ du -hs target/*.jar 14M target/greeting-spring-boot.jar

Much better than WildFly Swarm’s 45M. But where do we go from here? It’s still 14M for a hello world app.

While it is possible to separate app code from Spring code and produce an effect much like WildFly Swarm’s hollow JAR / skinny WAR duo, it requires you to violate the Fourth wall and know of the internals of the Spring Boot Uberjar, and write scripted surgery on the resulting FAT jar to split its contents along the app boundary defined by Boot. The result is a very tightly coupled and non-portable app and app server, with virtually no hope of upgrading and no ability to deploy anything to it other than the app from which it sprang. Runnable hollow JARs are not considered a first-class citizen in the Spring world.

Summary

We shrank our app from 45M → 512K → 2243 bytes using WildFly Swarm. With this approach, we can separate our app from its runtime dependencies, and put them in separate Linux container image layers. This will make your CI/CD pipelines fast, but also make your developers faster at edit/build/test and provide assurance that you are testing with the same bits that will land in production. Win-win-win in my book.

To build your Java EE Microservice visit WildFly Swarm and download the cheat sheet.

Last updated: June 12, 2023