This article is the second in a two-part article series on Kubernetes configuration patterns, which you can use to configure your Kubernetes applications and controllers. The first article introduced patterns and antipatterns that use only Kubernetes primitives. Those simple patterns are applicable to any application. This second article describes more advanced patterns that require coding against the Kubernetes API, which is what a Kubernetes controller should use.

The patterns you will learn in this article are suitable for scenarios where the basic Kubernetes features are not enough. These patterns will help you when you can't mount a ConfigMap from another namespace into a Pod, can't reload the configuration without killing the Pod, and so on.

As in the first article, for simplicity, I've used only Deployments in the example YAML files. However, the examples should work with other PodSpecables (anything that describes a PodSpec) such as DaemonSets and ReplicaSets. I have also omitted fields like image, imagePullPolicy, and others in the example Deployment YAML.

Configuration with central ConfigMaps

It isn't possible to mount a ConfigMap to a Deployment, Pod, ReplicaSet, or other components, when they are in separate namespaces. In some cases though, you need a single central configuration store for components that run in different namespaces. The following Deployment illustrates the situation:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: logcollector-config

namespace: logcollector

data:

buffer: "2048"

target: "file"

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: logcollector-agent

namespace: user-ns-1

spec:

...

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: server

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: logcollector-agent

namespace: user-ns-2

spec:

...

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: server

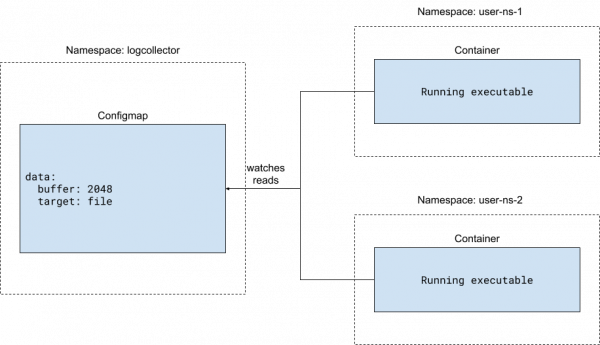

In this example, imagine there is a central log collector system, as shown in Figure 1. A Kubernetes controller (not shown in the example) creates a separate log collector agent Deployment for each namespace. That is why the ConfigMap and Deployment namespaces are different.

In the log collector agents within each namespace, the agent application reads the central ConfigMap for configuration. Please note that the ConfigMap is not mounted to the container. The application needs to use the Kubernetes API to read the ConfigMap, as the following pseudocode shows:

package main

import ...

func main(){

if _, err := kubeclient.Get(ctx).CoreV1().ConfigMaps("logcollector").Get("logcollector-config", metav1.GetOptions{}); err == nil {

watchConfigmap("logcollector" ,"logcollector-config", func(configMap *v1.ConfigMap) {

updateConfig(configMap)

})

} else if apierrors.IsNotFound(err) {

log.Fatal("Central ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace 'logcollector' does not exist")

} else {

log.Fatal("Error reading central ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace 'logcollector'")

}

}

This pseudocode gets the ConfigMap and starts watching it. If there is any change to the ConfigMap, the function updates the configuration. It is not necessary to roll out a new Deployment.

As the ConfigMap is in another namespace, containers need additional permissions for getting, reading and watching it. System administrators should handle the role-based access control (RBAC) settings for the containers. These settings are not shown here for brevity.

Configuration with central and namespaced ConfigMaps

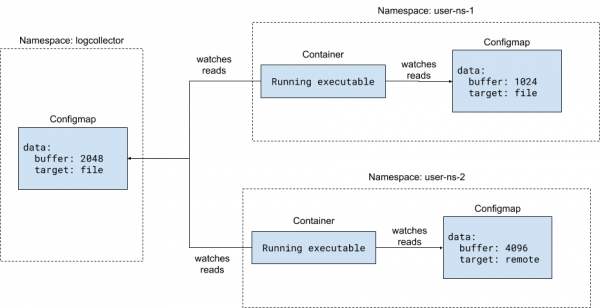

The Configuration with central ConfigMaps pattern lets you use a central configuration. In many cases, you also need to override some part of the configuration for each namespace.

This pattern uses a namespaced configuration in addition to the central configuration. A separate watch is needed for the namespaced ConfigMap in the code, as shown in Figure 2.

Here is the Deployment that sets up the namespaces and configurations:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: logcollector-config

namespace: logcollector

data:

buffer: "2048"

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: logcollector-config

namespace: user-ns-1

data:

buffer: "1024"

target: "file"

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: logcollector

name: logcollector-deployment

namespace: user-ns-1

spec:

...

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: server

env:

- name: NAMESPACE

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

For brevity, the Deployment in namespace user-ns-2 is not shown in the preceding YAML. It is exactly the same as the Deployment in namespace user-ns-1.

There are two ConfigMaps now. One is in the logcollector namespace that is considered the central configuration. The other is in the same namespace as the log collector instance in the user-ns-1 namespace. The code for retrieving the configurations is:

package main

import ...

func main(){

if namespace := os.Getenv("NAMESPACE"); ns == "" {

panic("Unable to determine application namespace")

}

var central *v1.ConfigMap

var local *v1.ConfigMap

if _, err := kubeclient.Get(ctx).CoreV1().ConfigMaps("logcollector").Get("logcollector-config", metav1.GetOptions{}); err == nil {

watchConfigmap("logcollector" ,"logcollector-config", func(configMap *v1.ConfigMap) {

central = configMap

config := mergeConfig(central, local)

updateConfig(config)

})

} else if apierrors.IsNotFound(err) {

log.Fatal("Central ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace 'logcollector' does not exist")

} else {

log.Fatal("Error reading central ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace 'logcollector'")

}

if _, err := kubeclient.Get(ctx).CoreV1().ConfigMaps(namespace).Get("logcollector-config", metav1.GetOptions{}); err == nil {

watchConfigmap(namespace ,"logcollector-config", func(configMap *v1.ConfigMap) {

central = configMap

config := mergeConfig(central, local)

updateConfig(config)

})

} else if apierrors.IsNotFound(err) {

log.Infof("Local ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace '%s' does not exist", namespace)

} else {

log.Fatalf("Error reading local ConfigMap 'logcollector-config' in namespace '%s'", namespace)

}

}

func mergeConfig(central, local *v1.ConfigMap) (...){

// merge 2 configmaps here and return the result

}

The Kubernetes controller application will check the central config first, then the namespaced config. The configuration in the namespaced ConfigMap will have precedence.

Notes about the pattern

It is okay to not have any local ConfigMaps. Unlike when the central ConfigMap is missing, the program will not stop execution if the local ConfigMap does not exist.

The application needs to know the container namespace in which it is running, because the local ConfigMap is not mounted using the ConfigMap mounting and the application needs to issue a GET for the local ConfigMap. Therefore, the application needs to tell the Kubernetes API the namespace it is looking in for the ConfigMap.

It would also be possible to simply mount the namespaced ConfigMap into the log collector container. But in that case, you would lose the ability to reload the config without any restarts.

Configuration with custom resources

You can use custom resources to extend the Kubernetes API. A custom resource is a very powerful concept, but too complicated to explain in depth here. A sample custom resource follows:

apiVersion: apiextensions.k8s.io/v1

kind: CustomResourceDefinition

metadata:

name: eventconsumers.example.com

spec:

group: example.com

versions:

- name: v1

...

scope: Namespaced

names:

plural: eventconsumers

singular: eventconsumer

kind: EventConsumer

...

After applying this custom resource definition, you can create an EventConsumer resource on Kubernetes:

apiVersion: example.com/v1 kind: EventConsumer metadata: name: consumer-1 namespace: user-ns-1 spec: source: source1.foobar.com:443 --- apiVersion: example.com/v1 kind: EventConsumer metadata: name: consumer-2 namespace: user-ns-2 spec: source: source2.foobar.com:443

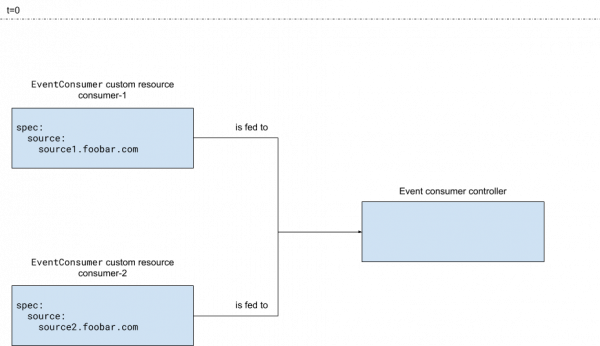

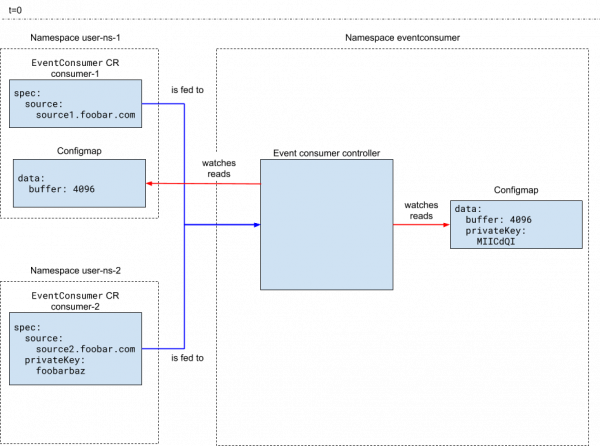

Custom resources can be used as configurations to be read by the Kubernetes controller, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows that the controller reads the custom resources.

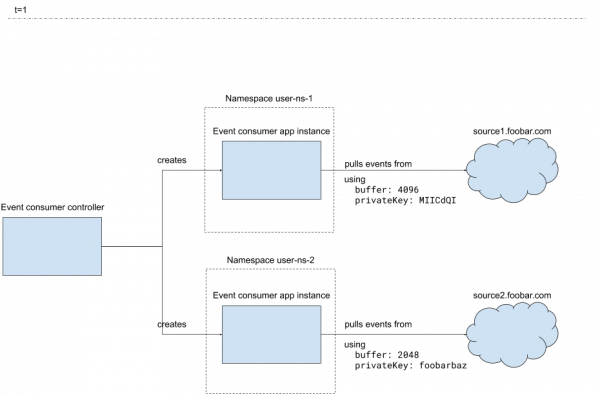

Figure 4 shows that after the controller reads and processes the custom resources, it creates an event consumer application instance per custom resource.

In this case, the EventConsumer custom resource provides a configuration for the event consumption applications that are created by the event consumer Kubernetes controller.

Note the scope: Namespaced key and value in the custom resource definition. This tells Kubernetes that the custom resources created for this definition will live in a namespace.

A strong API for fields in the config is a nice feature. With rules defined in the custom resource definition, you can use a Kubernetes validation without any hassle.

Drawbacks to configuration with custom resources

A custom resource is less flexible than a ConfigMap. It is possible to add data in any shape in a ConfigMap. Also, it is not necessary to register a ConfigMap in Kubernetes; you just create it. You must register custom resources by creating a CustomResourceDefinition. The information you add in a custom resource should match the shape defined in the CustomResourceDefinition. As stated earlier, a strong API is often considered a best practice. Even though ConfigMaps are more flexible, using well-defined shapes for configuration is a good idea whenever possible.

Additionally, not everything can be specified strongly in advance. Imagine a program that can connect to multiple databases. The database clients will have different configurations and their shapes will be different. It will not be possible to simply define fields in the custom resource to pass them as a whole to the database client. It is not a good idea to create a custom resource that has a super large shape definition, because it can be in multiple shapes.

Additionally, the custom resource definition must be maintained carefully, and you cannot simply delete fields or update fields in an incompatible way without releasing a new version of the custom resource. There is no problem with adding new fields.

Configuration with custom resources, falling back to ConfigMaps

This pattern is a mix of the Configuration with custom resources pattern and Configuration with central and namespaced ConfigMaps patterns.

In this pattern, configuration options that cannot be used in every scenario are placed in custom resources. Options that could be held in common by different custom resources are placed in ConfigMaps so that they can be shared. This pattern is shown in Figures 5 and 6. Figure 5 shows that the controller is watching and reading the user-namespaced ConfigMap and the custom resources. However, it relies first on the custom resources, falling back to ConfigMap for values missing in the custom resources.

Figure 6 shows the application landscape created by the controller for the configuration given in Figure 5.

Here is the Deployment that sets up the configurations, starting with the custom resource definition:

apiVersion: apiextensions.k8s.io/v1

kind: CustomResourceDefinition

metadata:

name: eventconsumers.example.com

spec:

group: example.com

versions:

- name: v1

...

scope: Namespaced

names:

plural: eventconsumers

singular: eventconsumer

kind: EventConsumer

...

---

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: EventConsumer

metadata:

name: consumer-1

namespace: user-ns-1

spec:

source: source1.foobar.com:443

---

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: EventConsumer

metadata:

name: consumer-2

namespace: user-ns-2

spec:

source: source2.foobar.com:443

privateKey: |

-----BEGIN PRIVATE KEY-----

foobarbazfoobar

barfoobarbazfoo

bazfoobarfoobar

-----END PRIVATE KEY-----

And here is the ConfigMap:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: eventconsumer-config

namespace: eventconsumer

data:

buffer: "2048"

privateKey: |

-----BEGIN PRIVATE KEY-----

MIICdQIBADANBgk

nC45zqIvd1QXloq

bokumO0HhjqI12a

-----END PRIVATE KEY-----

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: eventconsumer-config

namespace: user-ns-1

data:

buffer: "4096"

In the example, EventConsumer consumer-1 connects to the source1.foobar.com:8443 URL to consume events. Note, though, that consumer-2 is connecting to another URL.

The central ConfigMap in eventconsumer-config contains the buffer size as well as the private key. These will be used by the event consumer controllers unless there are overrides in local ConfigMaps or in the custom resources.

In the user-ns-1 namespace, a local ConfigMap overrides the buffer size for the EventConsumer in that namespace. No local ConfigMap exists for consumer-2 and no buffer size override exists in the custom resource, so the default buffer size in the central ConfigMap will be used for that consumer.

In the consumer-2 custom resource, there’s a privateKey defined, so the one in the central ConfigMap is not used.

Notes about the pattern

This pattern helps with sharing common information for custom resources. The buffer size or the private key could have been hardcoded in the application. Instead, in this case, even the defaults are configurable.

As explained in the Configuration with central and namespaced ConfigMaps pattern, a better approach could be creating a separate central configuration custom resource that is cluster-scoped and that contains the shared configuration. That might then additionally bring the namespaced configuration custom resources, and so on. If there are many options and if they are complex to build and validate, using a separate custom resource might be better than using a central configuration custom resource, because it can leverage the OpenAPI validation in Kubernetes.

References to ConfigMaps in custom resources

The previous pattern, Configuration with custom resources, falling back to ConfigMaps, helps with sharing the configuration for multiple custom resources. But it does not allow you to specify different shared configurations for custom resources in the same namespace.

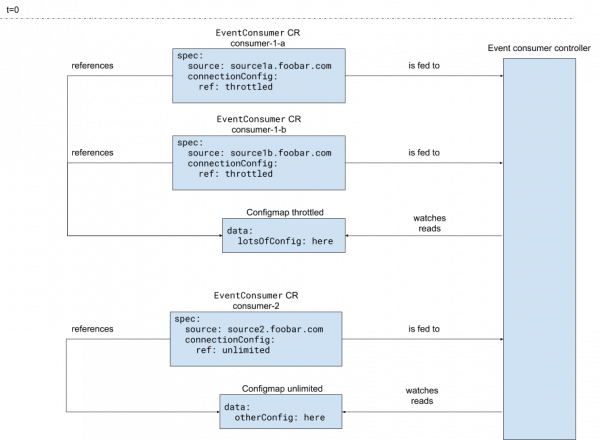

We can remedy that issue with this pattern, which keeps the long and complicated configurations in the ConfigMaps, as shown in Figures 7 and 8. Storing the configurations in a custom resource specification is not desirable.

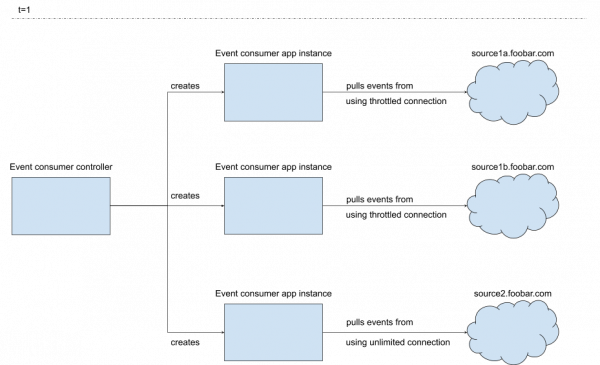

Figure 8 shows the application landscape created by the controller for the configuration given in the above figure.

Here is the Deployment that sets up the configurations, starting with the custom resource definition:

apiVersion: apiextensions.k8s.io/v1

kind: CustomResourceDefinition

metadata:

name: eventconsumers.example.com

spec:

group: example.com

versions:

- name: v1

...

scope: Namespaced

names:

plural: eventconsumers

singular: eventconsumer

kind: EventConsumer

...

---

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: EventConsumer

metadata:

name: consumer-1-a

spec:

source: source1a.foobar.com:443

connectionConfig:

ref: throttled

---

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: EventConsumer

metadata:

name: consumer-1-b

spec:

source: source1b.foobar.com:443

connectionConfig:

ref: throttled

---

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: EventConsumer

metadata:

name: consumer-2

spec:

source: source2.foobar.com:443

connectionConfig:

ref: unlimited

And here is the ConfigMap:

apiVersion: v1 kind: ConfigMap metadata: name: throttled data: lotsOfConfig: here --- apiVersion: v1 kind: ConfigMap metadata: name: unlimited data: otherTypeOfConfig: here

In this pattern, the custom resource contains a reference to the ConfigMap. The ConfigMap can be referenced in multiple custom resources in the same namespace. It is also possible to reference different ConfigMaps in custom resources that are in the same namespace.

Furthermore, the configuration in the ConfigMap can even be referenced in custom resources of different types. For example, the TLS settings could be kept in a ConfigMap and referenced in both a Kafka client component custom resource and a CouchDB client component custom resource.

Conclusion

Patterns in the first article and this one complete this article series on Kubernetes configuration patterns. I personally have seen more configuration patterns used in Kubernetes controllers in the projects I work on, sometimes even very strange ones. The handpicked patterns in this article are the best I've found. They are flexible enough to let you build on top of them to solve your configuration problems.

Last updated: February 5, 2024